posted by Andrea Pitzer on May 11 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

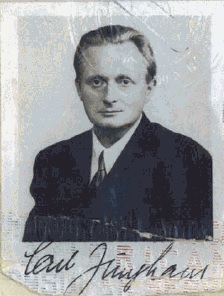

Vladimir Nabokov threw a Molotov cocktail into twentieth-century literature with Lolita. Alexander Solzhenitsyn survived Russian forced-labor camps and brought the word gulag into the global lexicon. Plenty of drama involving both of them appears in The Secret History, but as characters in the book they nonetheless faced competition from a lesser-known, scenery-chewing German named Carl Junghans.

In his late twenties, after stints as an extra, an actor, and a dramaturge, Junghans developed into a Communist filmmaker sympathetic to Soviet Russia. He also became involved with Vera Nabokov’s sister Sonia Slonim in Weimar-era Berlin. When exactly the pair met is a mystery, though the odds are good that it was in the mid-to-late 1920s, when Slonim, in her late teens, was taking classes at a drama school in the city and Junghans, eleven years older, was himself acting, editing, and working as a film critic in Berlin. (Their overlap in the city came on the heels of Vera and Vladimir Nabokov’s marriage.)

In his late twenties, after stints as an extra, an actor, and a dramaturge, Junghans developed into a Communist filmmaker sympathetic to Soviet Russia. He also became involved with Vera Nabokov’s sister Sonia Slonim in Weimar-era Berlin. When exactly the pair met is a mystery, though the odds are good that it was in the mid-to-late 1920s, when Slonim, in her late teens, was taking classes at a drama school in the city and Junghans, eleven years older, was himself acting, editing, and working as a film critic in Berlin. (Their overlap in the city came on the heels of Vera and Vladimir Nabokov’s marriage.)

Independent filmmaker and Communist propagandist

By 1930 people knew Slonim and Junghans as a public couple, referring to her as his girlfriend. Junghans had established himself as a serious artist by writing and directing one of the last transcendent silent films, Takový je zivot (Such Is Life), a Czech independent feature released in 1929. By that time, he had also completed montage tributes to Vladimir Lenin and the Russian Revolution.

Not long after, he may also have served as literary inspiration to Vladimir Nabokov. In Camera Obscura, Nabokov’s 1932 novel, teenage Magda aspires to be an actress and ends up in an affair with Bruno, an older German critic whose life she destroys. The novel, eventually called Laughter in the Dark in English, was written at the end of Slonim and Junghans’ Berlin relationship.

Did the eleven-year gap between Carl Junghans’ and Sonia Slonim’s ages inspire Nabokov to tackle the older man-younger girl theme? He had recently touched on a man’s post-death sexual encounter with a girl in the dreamlike lines of the 1928 poem “Lilith.” But Camera Obscura represents his first in-depth attention to the split-age pairing that would later dominate Lolita.

Filmmaker for the Nazis

Slonim left for Paris in 1931. As the Nazi party began to acquire significant power, life in Germany for Communists became difficult and sometimes dangerous.

Leaving while it was still easy to do so, Junghans divorced his wife and left for the Soviet Union to make a film on American racism with Langston Hughes. Production was repeatedly delayed, and the project turned into a disaster. The script was unacceptable to Hughes and the fellow travelers who had come with him to Russia. Filmmakers were disappointed that the well-educated visitors seemed uninterested or incapable of improvising Negro spirituals for the film. Efforts to make the movie slowed and slowed before staggering entirely to a halt.

While in Russia, Junghans acquired a second wife, which nearly trapped him in the Soviet Union for good. Between the failure of the film and his near-hostage state, his experience with Communism under Stalin seems to have thoroughly disillusioned him.

He returned to Nazi Germany and began making films, increasingly for Nazi-run studios or Nazi collaborations. His projects included several political titles, among them The Great Age (a documentary about Hitler) and Youth of the World, a film of the 1936 Winter Olympics. He also helped Leni Riefenstahl with her epic project on the summer games the same year.

Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on May 07 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

When the Nabokovs came to America in 1940, they sailed through immigration, pausing only to struggle with a locked trunk that needed to be inspected by customs. But arrival in a new country was less simple for thousands of other refugees fleeing Europe during World War II, including Véra Nabokov’s younger sister Sonia. Making her way to New York just eight months after the Nabokovs’ entry, Sonia’s relationship with US government agencies would be both deeper and more complex.

Sonia Sophia Slonim had been born in St. Petersburg six years after Véra. In the wake of the Revolution, she fled her homeland with her sisters along a risky route at the age of 10.

Sonia Sophia Slonim had been born in St. Petersburg six years after Véra. In the wake of the Revolution, she fled her homeland with her sisters along a risky route at the age of 10.

Living in Berlin for several years, she studied acting at the highly-respected Hoeflich-Gruening School of Drama as a teen, then went to work in the German offices of the perfume companies Houbigant and Cheramy. (This may have provided some small inspiration later for Humbert Humbert’s own brief career in perfumes in New York.)

Moving to Paris long before the Nabokovs, she worked translating film scripts for such masters of cinema as Max Ophüls. In America she would tell friends that in the decade before the war began, she had spent several years working with French intelligence. She was certainly mixed up in intelligence matters, though I was unable to find any hard evidence of a role as an agent for the French (which does not mean that she was not).

A French spy? A German spy?

Due to a romantic relationship with a German man also in Paris (more on him and their time together later this week), Sonia Slonim stayed in the city until hours before Hitler’s forces invaded. At the last minute, the couple ended up fleeing to Casablanca, eventually making their way to America in January 1941.

Also probably due to her romance, when Sonia’s ship crossed the Atlantic, someone relayed a cable from French facilities at Martinique to U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull, suggesting that Slonim should be “observed due to unofficial reports here that she may be a German spy.” Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on May 01 2013

Filed In: News

If you’re out there reading this, Evgeni Nabokov, I’m very, very sorry. Though you don’t really have anything directly to do with The Secret History, I thought it would be fun to write something about the fact that you, the New York Islanders’ goalie, share a last name with Vladimir Nabokov.

Given that the Islanders were heading into the playoffs, it seemed perfect to pitch “Nabokov Wins One for the Islanders” to the whip-smart McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, describing it as “Speak, Memory set in the NHL.” And they, too, thought it sounded like a good idea.

Given that the Islanders were heading into the playoffs, it seemed perfect to pitch “Nabokov Wins One for the Islanders” to the whip-smart McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, describing it as “Speak, Memory set in the NHL.” And they, too, thought it sounded like a good idea.

In the piece I wrote, a narrator much closer to Vladimir Nabokov than to you describes his stint in the crease during an Islanders playoff game. The piece ran, and was called, variously, “the best thing ever” and falling within “the ‘currently killing it’ category.” The CBC picked it up tonight and had me read it aloud for their “As It Happens” radio program, including a short Q&A about how I became interested in your career, along with that other Nabokov.

But clearly we were mistaken. You allowed four goals on 15 shots, and the Islanders ended up losing the game 5-0. I received a peremptory email from Luke in Montreal, blaming me for the loss. By writing my piece, he claims that I jinxed you. Luke also, rather consolingly, tells me I am the most amazing American woman he has never met—and adds that he will buy my book as soon “as it comes out in paperback on amazon probably.”

So for ruining the series opener, and for making Luke sad, I would like to apologize. Moving forward, I will stay away from playoff predictions in the titles of any pieces I write, and will try to focus on just Vladimir Vladimirovich.

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Apr 30 2013

Filed In: News

This week I’ll be in Chicago (the Book Cellar, May 3) and Minneapolis (Magers & Quinn, May 2). But I wanted to post a quick note to let mid-Atlantic readers know that registration has opened for my next book event, on Thursday, June 6 at the Smithsonian Associates program in Washington, DC.

The June DC talk will include discussion of both Lolita and Pale Fire in the context of Nabokov’s family, as well as World War II and concentration camp history. Audience Q&A will follow.

The June DC talk will include discussion of both Lolita and Pale Fire in the context of Nabokov’s family, as well as World War II and concentration camp history. Audience Q&A will follow.

Smithsonian Associates members get a discount, but anyone can attend. Come talk Nabokov in the nation’s capital—and take a quiz on the master that could win you a literary prize.

Get your tickets here.

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Apr 26 2013

Filed In: News

Thursday, May 2, I’ll be reading from The Secret History at Magers & Quinn Booksellers, Minneapolis/St. Paul’s largest independent bookstore.

The event starts at 7:30 pm. I promise not to do the Mary Tyler Moore thing with the hat, because everyone there has probably already seen that at least once or twice. But I am excited about my first visit to the Twin Cities.

The event starts at 7:30 pm. I promise not to do the Mary Tyler Moore thing with the hat, because everyone there has probably already seen that at least once or twice. But I am excited about my first visit to the Twin Cities.

The following night, May 3, I’ll be at the Book Cellar in Chicago starting at 7pm. They have books! They have wine! We will talk about Nabokov! What more could you want from life?

Yet there is more. For my upcoming book events through June 15, I’ll be handing out a quiz that will find out how well readers know Nabokov’s books. So if you see me in Minneapolis, Chicago, San Francisco, West Hollywood, or Washington, DC, be sure to fill one out. (For dates and times in each city, see the Events page.)

You don’t need to have read my book to answer the questions—any Nabokov lover will have a shot at winning. Entries have to be filled out in person without Internet assistance and turned in at the event. The highest score wins, and I will mail the winner his or her choice from some fabulous Nabokovian prizes. (To get an idea of what they might be, the prize for the photo contest was a beautifully embossed, newly annotated Grimm’s Fairy Tales).

Hearing from people who have already read The Secret History is wonderful, and it’s also great to get out and talk to readers who are interested in Nabokov and history and would like to know more. Thousands of people have visited this website from 67 countries and all but one American state (South Dakota, call me sometime, will you?). I hope to meet each of you in person one day.

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Apr 24 2013

Filed In: Beginner

In case you missed it earlier this week, Maria Popova of Brain Pickings wrote up The Secret History for Nabokov’s birthday. Popova focuses on the point in the book when Nabokov arrives in America in the midst of World War II, with all the attendant bureaucracy and anxiety over threats to national security. Along the way she also says some generous things about the book as a whole.

What few realize, however — and what Pitzer reveals through newly-declassified intelligence files and rigorously researched military records — is that Nabokov wove serious and unsettling political history into the fabric of his fiction, which had gone undetected for decades: until now. Absorbing and illuminating, The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov paints an unparalleled portrait of the author’s dimensional life and legacy, remarkably, without stripping his work of any of its magic.

See the whole post here.

Read more ›

In his late twenties, after stints as an extra, an actor, and a dramaturge, Junghans developed into a Communist filmmaker sympathetic to Soviet Russia. He also became involved with Vera Nabokov’s sister Sonia Slonim in Weimar-era Berlin. When exactly the pair met is a mystery, though the odds are good that it was in the mid-to-late 1920s, when Slonim, in her late teens, was taking classes at a drama school in the city and Junghans, eleven years older, was himself acting, editing, and working as a film critic in Berlin. (Their overlap in the city came on the heels of Vera and Vladimir Nabokov’s marriage.)

In his late twenties, after stints as an extra, an actor, and a dramaturge, Junghans developed into a Communist filmmaker sympathetic to Soviet Russia. He also became involved with Vera Nabokov’s sister Sonia Slonim in Weimar-era Berlin. When exactly the pair met is a mystery, though the odds are good that it was in the mid-to-late 1920s, when Slonim, in her late teens, was taking classes at a drama school in the city and Junghans, eleven years older, was himself acting, editing, and working as a film critic in Berlin. (Their overlap in the city came on the heels of Vera and Vladimir Nabokov’s marriage.)