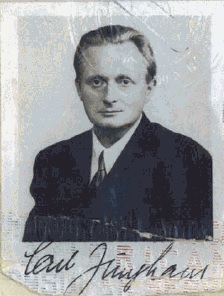

Meet Carl Junghans: informer, propagandist, and… literary inspiration for Nabokov?

Vladimir Nabokov threw a Molotov cocktail into twentieth-century literature with Lolita. Alexander Solzhenitsyn survived Russian forced-labor camps and brought the word gulag into the global lexicon. Plenty of drama involving both of them appears in The Secret History, but as characters in the book they nonetheless faced competition from a lesser-known, scenery-chewing German named Carl Junghans.

In his late twenties, after stints as an extra, an actor, and a dramaturge, Junghans developed into a Communist filmmaker sympathetic to Soviet Russia. He also became involved with Vera Nabokov’s sister Sonia Slonim in Weimar-era Berlin. When exactly the pair met is a mystery, though the odds are good that it was in the mid-to-late 1920s, when Slonim, in her late teens, was taking classes at a drama school in the city and Junghans, eleven years older, was himself acting, editing, and working as a film critic in Berlin. (Their overlap in the city came on the heels of Vera and Vladimir Nabokov’s marriage.)

In his late twenties, after stints as an extra, an actor, and a dramaturge, Junghans developed into a Communist filmmaker sympathetic to Soviet Russia. He also became involved with Vera Nabokov’s sister Sonia Slonim in Weimar-era Berlin. When exactly the pair met is a mystery, though the odds are good that it was in the mid-to-late 1920s, when Slonim, in her late teens, was taking classes at a drama school in the city and Junghans, eleven years older, was himself acting, editing, and working as a film critic in Berlin. (Their overlap in the city came on the heels of Vera and Vladimir Nabokov’s marriage.)

Independent filmmaker and Communist propagandist

By 1930 people knew Slonim and Junghans as a public couple, referring to her as his girlfriend. Junghans had established himself as a serious artist by writing and directing one of the last transcendent silent films, Takový je zivot (Such Is Life), a Czech independent feature released in 1929. By that time, he had also completed montage tributes to Vladimir Lenin and the Russian Revolution.

Not long after, he may also have served as literary inspiration to Vladimir Nabokov. In Camera Obscura, Nabokov’s 1932 novel, teenage Magda aspires to be an actress and ends up in an affair with Bruno, an older German critic whose life she destroys. The novel, eventually called Laughter in the Dark in English, was written at the end of Slonim and Junghans’ Berlin relationship.

Did the eleven-year gap between Carl Junghans’ and Sonia Slonim’s ages inspire Nabokov to tackle the older man-younger girl theme? He had recently touched on a man’s post-death sexual encounter with a girl in the dreamlike lines of the 1928 poem “Lilith.” But Camera Obscura represents his first in-depth attention to the split-age pairing that would later dominate Lolita.

Filmmaker for the Nazis

Slonim left for Paris in 1931. As the Nazi party began to acquire significant power, life in Germany for Communists became difficult and sometimes dangerous.

Leaving while it was still easy to do so, Junghans divorced his wife and left for the Soviet Union to make a film on American racism with Langston Hughes. Production was repeatedly delayed, and the project turned into a disaster. The script was unacceptable to Hughes and the fellow travelers who had come with him to Russia. Filmmakers were disappointed that the well-educated visitors seemed uninterested or incapable of improvising Negro spirituals for the film. Efforts to make the movie slowed and slowed before staggering entirely to a halt.

While in Russia, Junghans acquired a second wife, which nearly trapped him in the Soviet Union for good. Between the failure of the film and his near-hostage state, his experience with Communism under Stalin seems to have thoroughly disillusioned him.

He returned to Nazi Germany and began making films, increasingly for Nazi-run studios or Nazi collaborations. His projects included several political titles, among them The Great Age (a documentary about Hitler) and Youth of the World, a film of the 1936 Winter Olympics. He also helped Leni Riefenstahl with her epic project on the summer games the same year.

Eventually (in his telling of the story) he found himself on the wrong side of Goebbels and fled Germany to Switzerland with false papers. He made his way to France a year and a half after the Nabokovs finally left Berlin; all of them met up again with Sonia Slonim in Paris. Slonim, who was Jewish, would later tell friends she had been working with French intelligence for years and was asked to keep an eye on Junghans. If so, it’s not clear whether her French handlers were aware the two had been involved before.

What is clear is that he was not trusted by French external intelligence (the Deuxième Bureau). When the war broke out not long after his arrival, Bureau agents made clear that he had to stay in Paris and that if he tried to leave the city he would be shot.

Junghans began to do propaganda for the French. In addition, it appears that either he offered to become or was leveraged into being an informant. He would claim to have been employed by the Bureau, but refugees interviewed later believed that he was only a low-level informer who had a role pointing out politically suspect people who should be interned in French concentration camps.

Because the French police had forbidden his departure, Junghans could not leave the city until hours before it fell to the German army. At the last minute, he and Slonim made their way south to Casablanca, and eventually to New York.

Junghans in Hollywood: “tap dancing and the art of juggling”

Carl Junghans was not unknown in the US. Though the country had not yet entered the war, his background and a letter from the Anti-Defamation League reporting him as a “thorough-going Nazi” led to his detention at Ellis Island for most of the first half of 1941. Slonim finally got some help in extricating him when a friend who knew them in their Berlin days became involved.

The Nabokovs, Slonim, and Junghans were all in New York for a brief time before the Nabokovs left for Stanford, where Nabokov taught that summer. But Slonim and Junghans were not far behind, with dreams of Hollywood.

On arrival, Junghans reconnected with William Dieterle, a director of Oscar-winning movies who had sent money to him in New York. He suddenly got several promising leads for screenwriting. But after Pearl Harbor, the US entered the war, and Junghans was rounded up in California with thousands of other suspected German spies, who were herded into police facilities and internment camps. The testimony he gave in an attempt to get released (much of which also appeared in previous propaganda articles he had written for Free French groups and speeches he had given) got the attention of the FBI. These experiences and stories would find strange echoes in refugee Humbert Humbert’s account of his own war years, including Swiss passports, arctic bases, and hush-hush intelligence activities transpiring in the ice.

What Junghans told the FBI was convincing enough to earn him a spot as an informant in yet another country. Yet much of what he relayed was bonkers. In the image below (click to see the whole page), he writes of Aryans circumcised and trained to be Jewish so that they might enter America as spies. Some are trained in “tap dancing and the art of juggling,” in order to be able to join a vaudeville troupe. Others are sent to train in chemistry; while still more are sent to learn film production or the textile trade. According to Junghans, these false Jews were even “thrown into German Concentration Camps” to have a “perfect alibi,” and then given passports marked “J” before being smuggled over the border.

Junghans was eventually paroled but was not allowed to leave the West Coast for several years. Sonia Slonim returned to New York while he was still in detention. His reputation shredded after working for the Nazi propaganda machine, Junghans did not find film work in Hollywood, instead becoming a gardener for Bertolt Brecht and other German refugees in California.

He later returned to Germany and won a lifetime achievement award from the German Film Academy a decade before dying in Munich in 1984. During interviews conducted in the last years of his life, he was resentful about having his place in film history ignored.

The rough material for Humbert Humbert came from many places, but it is amusing to think Junghans may have been a partial spark for not one but two of Nabokov’s appalling protagonists. As he and Sonia Slonim separated and reunited across more than a decade in city after city where the Nabokovs also lived, it is tempting to imagine Junghans as the opposite of Nabokov: a talented artist who placed his gifts entirely in the service of ideology and never again triumphed as a creator. Or, on a simpler level, perhaps we can think of him as Nabokov’s Billy Carter.

The images above are taken from Carl Junghans’ US Citizenship and Immigration Services file and appear courtesy UCIS