posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jun 10 2013

Filed In: News

Hello, California! I’m heading out Wednesday to bring The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov to you. Here’s the schedule of events for the week:

Wednesday, June 12, I’ll be at The Booksmith on Haight Street in San Francisco, reading at 7:30 p.m.

Wednesday, June 12, I’ll be at The Booksmith on Haight Street in San Francisco, reading at 7:30 p.m.

Thursday, June 13, I’ll be part of the group event “Why There Are Words” at Studio 333 on Caledonia Street in Sausalito. Doors open at 7:00, and tickets are required. The theme is “Transitions.”

Friday, June 14, I’ll be at Book Soup on Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood, starting at 7:00 pm.

After that I’ll be on summer hiatus from events, researching my next book. But it looks like I’ll head to Canada this fall for a few dates. I’ll update the site as soon as I have more information…

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jun 04 2013

Filed In: News

For those of you living in and around the nation’s capital–seats are still available for my talk at the Smithsonian Associates program this Thursday (June 6), starting at 6:45 pm in Washington, DC.

I’ll be looking at both Lolita and Pale Fire in the context of Nabokov’s family, as well as World War II and concentration camp history.

I’ll be looking at both Lolita and Pale Fire in the context of Nabokov’s family, as well as World War II and concentration camp history.

See images from newly declassified intelligence files. Learn about possible inspirations for Humbert Humbert and the real-world Camp Q, as well as the ways in which Pale Fire reflected Nabokov’s personal tragedies and his lost Russia.

Smithsonian Associates members get a discount, but anyone can attend. Come talk Nabokov in Northwest DC—and take a quiz on the master that could win you a literary prize.

Get your tickets here.

posted by Andrea Pitzer on May 29 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

What do Richard Feynman, theoretical physicist, and Vladimir Nabokov, author of Lolita, have in common? For one, synesthesia—a blending of sensory input experienced by four percent of the population. Letters for Nabokov came paired with specific colors, and Feynman similarly reported seeing “light tan j’s, slightly violet-bluish n’s, and dark brown x’s flying around” in equations.

Looking into Feynman’s synesthesia recently, I came across a video that addresses, in an oblique way, a question people have raised about The Secret History. The suggestion that Nabokov’s protagonists (Lolita, Pale Fire, Despair) have backstories tied to the horrors of their century—ones that can be hazily glimpsed through the lines of the text—led one reviewer to suggest that this “interpretation makes Humbert and Kinbote rather less interesting as characters, easier to place, more comprehensible.” He wrote that a “‘secret history’ implies a history that can be uncovered and then understood.” But Nabokov, he argued, was after far more than that.

So then, does binding Nabokov’s madmen to their times and places—places they themselves introduce into their stories—also box them in and damage the artistry of the novels? I would agree, if doing so flattened them out, or simplified them, or excused their actions. But that’s not what I intended The Secret History to do.

As surely as Humbert’s sins are his own, and unforgivable, it is also true that he has been broken by history. His suffering has not ennobled him; instead, it has driven him mad, just as historic events had destroyed Despair’s Hermann decades before, and character after character in Nabokov’s novels and short stories in between.

I’m arguing for more complex main characters, ones who are both monsters and something else. Like the monstrousness, that something else requires a response from readers, in the form of attention to Nabokov’s narratives and the readers’ own ways of being in the world. Holding a more complex view of Nabokov’s creatures that excuses nothing but sees them whole—or as close as we can get to seeing them whole—is a challenging and valuable thing.

Nabokov liked to use traceable details to frame his books and then to cloak his scaffolding in rich language and imagery. But the importance of observing and understanding the real world was never lost. His once-student and later annotator Alfred Appel told a story about a friend who went to see Nabokov when he was a professor at Cornell. Nabokov directed the student to look out the window. “Do you know the name of that tree?” Nabokov is said to have asked. The friend replied that he did not. Nabokov’s response was, “Then you’ll never be a writer.” I believe that attending to the settings of Nabokov’s novels is as important as knowing the names of trees.

A Feynman video from YouTube addresses a similar idea. In it, the physicist (who first worked on the Manhattan Project and later revolutionized the field of quantum physics) talks about an artist friend of his. The friend, he explains, once held up a flower and said, “I as an artist can see how beautiful it is, but you as a scientist… take this all apart, and it becomes this dull thing.” Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on May 21 2013

Filed In: Beginner

I have several projects only tangentially related to The Secret History simmering in the background, from a Nabokov novel generator that’s in process (no kidding) to a potential annotation effort. But with so many possibilities out there, why stop now?

At a few points this summer, I’ll be forced away from the computer. And while there’s always plenty to read and a next book to start, it’s good for a girl to keep her nose out of the books every now and then.

In a prior life, I was a painter (see left). And in the spirit of the decks of cards Maria Popova has featured over at Brain Pickings, I was thinking that it might be interesting to come up with a set for Nabokov.

In a prior life, I was a painter (see left). And in the spirit of the decks of cards Maria Popova has featured over at Brain Pickings, I was thinking that it might be interesting to come up with a set for Nabokov.

I have some early glimmerings, but this is the kind of project that can benefit from multiple ideas up front. So I’m soliciting your suggestions.

We’re talking Nabokov, so we want something that combines humor with horror (real or imagined). In respect for his loathing of abstract art (and my own limits), we’ll keep it representational, but it doesn’t have to be slavishly so (meaning it doesn’t have to look like this painting). The cards can be line drawings or have more of a graphic design focus.

There are a few things I’d like you to chime in on, though you can feel free to offer any kind of suggestions. Read more ›

Tags:

posted by Andrea Pitzer on May 17 2013

Filed In: News

Nabokov had a complicated relationship with his critics, not least Edmund Wilson, whose 1965 review of Eugene Onegin in The New York Review of Books put a stake through the heart of their friendship. Here’s Wilson’s opening line:

This production, though in certain ways valuable, is something of a disappointment; and the reviewer, though a personal friend of Mr. Nabokov—for whom he feels a warm affection sometimes chilled by exasperation—and an admirer of much of his work, does not propose to mask his disappointment.

Yesterday, I had my own experience being reviewed in the NYRB. University College London professor Mark Ford had the honor of doing the carving up, in a group review. It’s out from behind the paywall now, so you can read it yourself, but I’ll do a quick survey and include a quote or two from it here.

Ford didn’t open with Wilson’s directness, starting instead with a summary of Nabokov’s life before diving into my book. He noted a few of the echoes between Nabokov’s younger brother, Sergei, and Pale Fire narrator Charles Kinbote high in the piece, which I was glad to see, because The Secret History is the first real exploration of that link, and it’s an important part of the book.

Ford didn’t open with Wilson’s directness, starting instead with a summary of Nabokov’s life before diving into my book. He noted a few of the echoes between Nabokov’s younger brother, Sergei, and Pale Fire narrator Charles Kinbote high in the piece, which I was glad to see, because The Secret History is the first real exploration of that link, and it’s an important part of the book.

Ford had some nice things to say, though he wasn’t a fan of my style. He liked the use of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Soviet dissident and Gulag survivor, in counterpoint to Nabokov as the framework of the narrative. He also praised my “exemplary primary research,” which, he suggests, “forces one to consider several fascinating quandaries presented by Lolita and Pale Fire.”

At some point, if I get just a little bigger pool to draw from, I’ll do a quantitative analysis of reviews of The Secret History, to see what that might offer in some larger sense about book reviews and reviewers. For now, I’m resisting posting more of the review here for fear of disappearing down a rabbit hole of quote and response that would surely be more boring than the unbelievably dull but angry quibbles that Wilson and Nabokov had over the finest points of Eugene Onegin.

Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on May 15 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

What’s so secret about The Secret History?

The most important history in the book is information that was once public knowledge but which has fallen out of public memory–Nabokov’s secret history as our forgotten past.

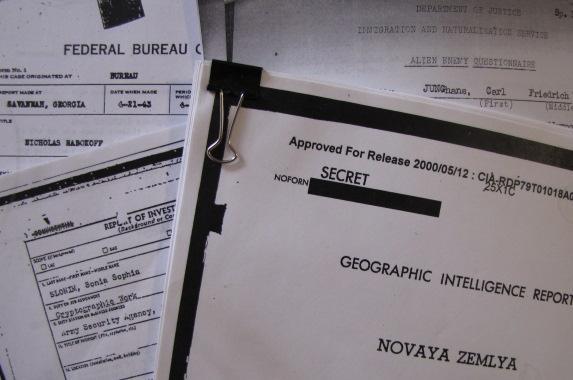

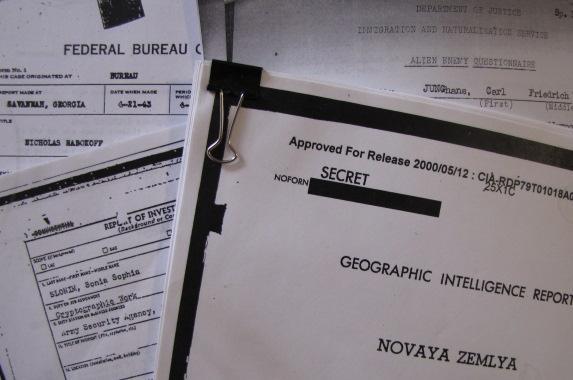

But there is also some actual secret history in there: classified documents and public records that shed light on Nabokov’s life or work. Last month, I finally posted the bibliography for the book, which will make it easier for people to search online for details on particular sources. And today, I’ll be including the list of files and numbers for declassified documents and public records referenced in the book as well. I’ll eventually put most of these in the Records section of this site, unless a given file is hundreds of pages, in which case I will upload only highlights.

In one or two instances, I’ll skip pages that include private medical information that is irrelevant to The Secret History. It’s worth keeping in mind that not everything in the files is true.

Here’s the list of documents by agency and number, with a little information about each:

FBI

VLADIMIR NABOKOV – see Sonia Slonim FBI file below (relevant pages already posted here)

VÉRA NABOKOV – see Sonia Slonim file below (relevant pages already posted here)

SONIA SLONIM – File #121-HQ-10141, including a loyalty review by the FBI and Department of the Army Intelligence and Security Command documents. Some information already written up/posted here.

NICHOLAS NABOKOV – File #123-1231. File starts from April 1943 and continues through July 1948, then picks for several final pages covering April to June 1967. Includes background check information from Nicholas’ intelligence work during the war, as well as a more in-depth Cold War investigation.

EDMUND WILSON – File #105-177115 This portion of Wilson’s FBI file deals with just an investigation of whether or not Wilson attended a 1968 Cultural Congress in Havana, Cuba. Those wishing to see additional info on Wilson should also request File #s 100-381720 and 100-381720-5. Read more ›

Tags: Boris Petkevitch, Carl Junghans, CIA, Edmund Wilson, FBI, Nicholas Nabokov, Sonia Slonim, US Citizenship & Immigration Services, US National Archives, Véra Nabokov, Vladimir Nabokov

Wednesday, June 12, I’ll be at The Booksmith on Haight Street in San Francisco, reading at 7:30 p.m.

Wednesday, June 12, I’ll be at The Booksmith on Haight Street in San Francisco, reading at 7:30 p.m.