posted by Andrea Pitzer on Feb 14 2013

Filed In: Beginner

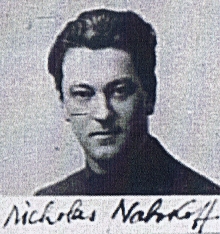

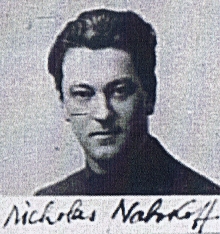

Next up in the Records series of archival material is the naturalization paperwork of Nicholas Nabokov. Nicholas was Vladimir Nabokov’s first cousin on his father’s side. A classical music composer who studied at the Sorbonne, he worked with several legendary cultural figures, including Ballets Russes founder Sergei Diaghilev.

Nicholas came to America in 1933, several years before Vladimir and Véra’s crossing. By the time of his naturalization in 1939, Nicholas Nabokov and his first wife—Russian princess Nathalie Shakhovskoy—had divorced, and he had remarried. His second wife, Constance Holladay, whom he listed as his spouse on his application for naturalization, was a U.S. citizen by birth. Nicholas would go on to have five wives in all before his death in 1978.

Other items in his file are of more historic interest. His certificate of US citizenship lists his former nationality as the “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.” While Nicholas had been born in 1903 on Polish territory in the Russian Empire, he had fled his homeland at the same time that his cousin Vladimir escaped in 1919. And the Soviet Union was officially formed at the end of 1922.

Other items in his file are of more historic interest. His certificate of US citizenship lists his former nationality as the “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.” While Nicholas had been born in 1903 on Polish territory in the Russian Empire, he had fled his homeland at the same time that his cousin Vladimir escaped in 1919. And the Soviet Union was officially formed at the end of 1922.

I suspected that he had said his nationality was Russian, and that a clerk had typed the USSR entry in error. But just in case, last year I asked my Russian research assistant to file an inquiry into whether Nicholas Nabokov had ever actually become a citizen of the USSR. It seemed highly unlikely, but there were unsubstantiated statements in his FBI file about his trying to return to Russia under Stalin, so I wanted to follow up. To date, nothing has appeared that suggests the USSR entry is anything but a mistake.

Office of Strategic Services

Perhaps the most interesting pages in Nicholas’ file are two requests made by the Office of Strategic Services in July and August of 1944 for his naturalization information. The OSS was responsible for coordinating military intelligence during the war, and was the forerunner of the CIA.

What is not mentioned in the file is that these requests were likely made to clear him for work with the staff of the US Strategic Bombing Survey. The Survey was established that November by the Secretary of War to assess the effectiveness of Allied air strikes. Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Feb 12 2013

Filed In: Beginner

For some people, sound has taste. Vladimir Nabokov saw the alphabet in color. Both are examples of synesthesia, in which a person experiences a second, paired sensation accompanying an initial different kind of sensory input.

A study out last month in Psychological Science suggests that though it is possible synesthesia is hardwired into individuals, many synesthetes’ particular color schemes seem to have their genesis in childhood toys. The study involved 11 people like Nabokov, said to have “color-grapheme” synesthesia—seeing color when looking at letters or numbers. Researchers managed to trace study subjects’ color associations to magnetic alphabet sets they used as children.

Born in 1899, Nabokov seems unlikely to have possessed the colored refrigerator magnet alphabets that became ubiquitous more than half a century later. So what were Nabokov’s childhood toys?

Born in 1899, Nabokov seems unlikely to have possessed the colored refrigerator magnet alphabets that became ubiquitous more than half a century later. So what were Nabokov’s childhood toys?

In his autobiography, Speak, Memory, Nabokov lists the colors he saw for each letter. Among the greens are “alder-leaf f, the unripe apple of p, and pistachio t.” In the same section, he specifically mentions a set of old blocks he was building with one day as a child. Their colors, he told his mother, were “all wrong.” She turned out not only to have synesthesia, but also to share some color-letter combinations with him. This new study makes me wonder whether he had been exposed to a set of colored blocks—perhaps the same set, or a similar set—that his mother had encountered as a child, one that had formed his sense of what color went with a given letter.

Nabokov’s son Dmitri also had synesthesia and described his family’s experience with it in an afterword to Wednesday Is Indigo Blue, a book which suggests that one in twenty people has some form of the condition. Writing of the effect synesthesia had on Nabokov, Dmitri specifically notes its literary impact:

Perhaps the most significant domain in which synesthesia may have affected Vladimir Nabokov was that of metaphor. When he describes an object, be it a chance item or an important prop, odds are that his description will have not only a touch of originality but also a color.

Like the subjects in the January study, Dmitri mentions that the Nabokovs retained their specific color-letter pairings across many years.

I don’t dwell on Nabokov’s synesthesia in The Secret History, but I find the idea that it might have been triggered by or taken root in early childhood associations fascinating. In this new understanding of synesthesia, for at least some people who experience it, the past and the building blocks of words come together in memory to form a literal palette of language. Memory may have concretely shaped Nabokov’s literary vision long before he ever wrote a word.

Image credit: adapted via Creative Commons license from a Leo Reynolds’ photo on Flickr

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Feb 07 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

Nabokov was crazy for complex allusions, intentionally seeding his fiction with literary and historical references, from pop culture and epic poetry to both in a single line (see “Chapman’s Homer” from Pale Fire). But there are so many winks and nods and proper names in his books, sorting out what has coherence from what is coincidence can be a vexing challenge.

In many ways, of course, it doesn’t matter. Readers reinvent a story based on their own knowledge and experience, and whether Nabokov intended them to make certain connections or not doesn’t render any particular association illegitimate.

But when writing The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, I was exploring in part the degree to which Nabokov had planted concentration camp history and references in his work. For my purposes, the question of what Nabokov meant became relevant.

But when writing The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, I was exploring in part the degree to which Nabokov had planted concentration camp history and references in his work. For my purposes, the question of what Nabokov meant became relevant.

In some cases, there is no question of what he was doing. When the Nabokovs wrote a note to a translator of Bend Sinister to point out that the phrase “ghoul-haunted Province of Perm” was meant in part to evoke the notorious Soviet labor camps of Perm, we can be fairly certain what Nabokov was up to.*

And though it has been largely ignored, when Hermann, the narrator of Despair, mentions being interned near Astrakhan in southern Russia from 1914 to 1919, there is little doubt that Nabokov sentenced his character to the kind of early pre-Gulag, pre-Holocaust concentration camps that did in fact exist in and around Astrakhan during those years.

But other references are more enigmatic or convoluted. Nabokov’s novel Pnin provides a lovely example of something that fascinated me and was promising but that I ultimately didn’t use. Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Feb 05 2013

Filed In: Beginner

Last week, I wrote up Vladimir Nabokov’s immigration file as the first in a series of archival materials that will appear on the Records page of this website. Today, I wanted to highlight a few details from the file of his wife, Véra Nabokov.

Véra had the same strange discrepancy in recorded height that appeared on Nabokov’s forms, going from 5’6” in France to 5’10” on her American papers. Like her husband, she listed his younger brother Sergei as her nearest relative, despite the fact that Sergei had expressed regret over Véra’s marriage to Vladimir.

Véra’s own younger sister, Sonia Slonim, was also still in Paris at the time. But she was caught up in espionage drama with which Véra might not have wanted to be associated in that moment. (I’ll post Sonia’s immigration file soon, but for details on Sonia’s political intrigues, you should read The Secret History.)

Véra’s own younger sister, Sonia Slonim, was also still in Paris at the time. But she was caught up in espionage drama with which Véra might not have wanted to be associated in that moment. (I’ll post Sonia’s immigration file soon, but for details on Sonia’s political intrigues, you should read The Secret History.)

Véra’s hair went from “blond” on visa forms in 1940 to “grey” five years later on her naturalization papers—which is hardly surprising, given that she also turned forty in that window. As was required by the race-obsessed immigration policies of the day, she is categorized as “Hebrew.”

She is “Russian” on one form, though on the official visa, it is made clear (as it was on her husband’s) that she is “without nationality,” having fled Russia before the formation of the Soviet Union. Like Nabokov, she had to present a stamped certificate from the Office of Russian Refugees attesting that she was a refugee but had been born in Russia to Russian parents, as well as providing a copy of her criminal record issued by the Ministry of Justice, showing she had never been arrested. Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Feb 01 2013

Filed In: Beginner

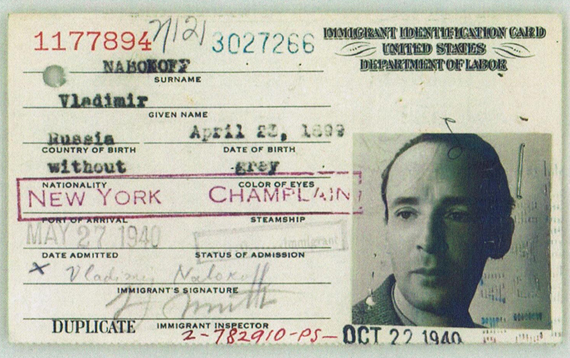

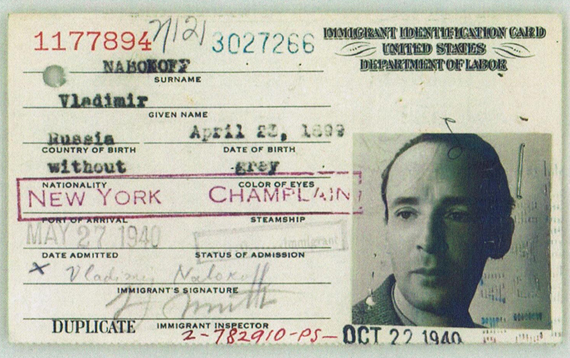

It’s pretty neat what you can learn from government archives. The first image series to be posted on the Records page of this site is Vladimir Nabokov’s immigration file, with documents spanning 1940 to 1945. Aside from pictures of the author, which are always interesting, the government forms offer their own sly narrative of Nabokov’s first years in America.

Born in Russia, Nabokov arrived officially as a man with no country (“without nationality” on the forms). He had fled his homeland before the formation of the Soviet Union in 1922 and so never became a Soviet citizen. Those who have read his short stories or autobiography know of the nightmare bureaucracy facing travelers, like his wife Véra and himself, who held only Nansen refugee passports.

The forms also show that though it had not yet entered the war when Nabokov arrived on its shores, America was very keen on keeping revolutionaries out. Travelers had to vow shipboard that they were not anarchists, and again on arrival, and again when they filled out their declarations of intent to become American citizens.

Pale and still recovering from influenza when his French doctor prepared his paperwork, Nabokov had more than the flu to keep him lean. After fleeing Hitler’s Germany for France, he and his wife Véra had struggled to keep their pre-school-age son Dmitri comfortable, but it’s pretty clear they themselves had been living at a bare subsistence level, due at least in part to legal restrictions barring them from work. Months after his arrival in America, Nabokov’s height was listed at 5’11”* and his weight at a still-skeletal 124 pounds. By the time he became a U.S. citizen in 1945—a few months after he had quit smoking and taken up molasses candy—he had gained more than 50 pounds. Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jan 31 2013

Filed In: News

On the “exciting news” front, The Secret History is now slated for publication in Russia and Poland. Russian house Sindbad Publishers Limited and Polish publisher Muza will be translating and printing the book in their respective countries. I’m particularly grateful that publishers in places so profoundly bound up with Holocaust and Gulag tragedy are interested in Nabokov’s life and writing in the context of this history.

Current events underline one reason why telling this story is so important worldwide. Reports from St. Petersburg in recent weeks detail new attacks on Nabokov-related places and productions in the city of his birth. Staging of a one-man show of Lolita was threatened last fall by cultural vigilantes. Though the performance did finally take place last month, the 23-year-old show manager was lured to a meeting (under pretext of an interview) only to be beaten and forced to confess to pedophilia on camera at gunpoint.

A similarly disturbing attack on the Nabokov Museum I mentioned in an earlier post was accompanied by warnings to museum staff, and just this week, the word pedophile scrawled on a wall of the beautiful mansion. Popular perception of who Nabokov was and what he was up to sorely lags the known facts, and ultraconservatives are pushing a retrograde view. Here’s hoping that The Secret History can play a small part in supporting the work of places like the Nabokov Museum and disseminating the truth.

Other items in his file are of more historic interest. His certificate of US citizenship lists his former nationality as the “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.” While Nicholas had been born in 1903 on Polish territory in the Russian Empire, he had fled his homeland at the same time that his cousin Vladimir escaped in 1919. And the Soviet Union was officially formed at the end of 1922.

Other items in his file are of more historic interest. His certificate of US citizenship lists his former nationality as the “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.” While Nicholas had been born in 1903 on Polish territory in the Russian Empire, he had fled his homeland at the same time that his cousin Vladimir escaped in 1919. And the Soviet Union was officially formed at the end of 1922. Born in 1899, Nabokov seems unlikely to have possessed the colored refrigerator magnet alphabets that became ubiquitous more than half a century later. So what were Nabokov’s childhood toys?

Born in 1899, Nabokov seems unlikely to have possessed the colored refrigerator magnet alphabets that became ubiquitous more than half a century later. So what were Nabokov’s childhood toys? But when writing The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, I was exploring in part the degree to which Nabokov had planted concentration camp history and references in his work. For my purposes, the question of what Nabokov meant became relevant.

But when writing The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, I was exploring in part the degree to which Nabokov had planted concentration camp history and references in his work. For my purposes, the question of what Nabokov meant became relevant.