posted by Andrea Pitzer on Mar 06 2013

Filed In: News

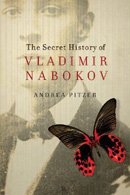

What were you planning to do today? Well, today is publication day for The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov!

I hope you’ll plow through any pesky snowfall that happened to arrive overnight and go to your local bookstore to buy it, or check it out of your library, or borrow it from a friend. If you find yourself entirely snowed in, you can order it online. Mostly, I hope you’ll read it.

People who send me pictures of themselves fully clothed and holding a copy of the book in the next two weeks will be entered in a drawing to win a very Nabokovian prize.

Email images to andrea [dot] pitzer [at] gmail [dot] com.

Happy reading!

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Mar 05 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

Tomorrow The Secret History will be published! I’m headed up to New York to do my first interview for the book. But before it drops, I wanted post a quick note on something important.

I’ve spent the last five years exploring the links between Nabokov’s fiction and the world in which he lived. There’s a danger to this approach—you can get caught up in things like, “This tree can be seen from the rear windows of the Museum of Contemporary Zoology at Harvard (where Nabokov helped curate butterfly collections in the 1940s). He must have looked out on it during the years he was writing Bend Sinister.” And no doubt about it—there’s a certain charm to tracing Nabokov’s life or seeing things that might have inspired him.

But a relentless search for links like these sometimes doesn’t lead to any greater understanding of what a writer has accomplished—after all, the magic is in the transformation. I, too, might look down on that same tree, but I can’t write Bend Sinister, let alone Lolita.

But a relentless search for links like these sometimes doesn’t lead to any greater understanding of what a writer has accomplished—after all, the magic is in the transformation. I, too, might look down on that same tree, but I can’t write Bend Sinister, let alone Lolita.

Nabokov himself resisted these connections, telling his Cornell students that Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time was not autobiography but fantasy, “just as Cornell University will be a fantasy if I ever happen to write about it some day in retrospect.”

The enchantment the author casts is the most sublime aspect of a great book, Nabokov argued, and to look to fiction to say something about history or the time and place in which it is set is foolish.

Except when it isn’t. I suspect that when he made those statements, Nabokov himself only half-believed them. Even then, he pointed out to his students reading Mansfield Park that one character’s trip to Antigua recalls the plantations there and the cheap slave labor that had built the family’s fortune.

What’s more, by the time he arrived at Cornell, he had been working toward something different for nearly two decades. The fiction he wrote after his teaching years would most directly counter his own arguments. By the time he got to 1962’s Pale Fire, he let one character directly make a plea for a revised view. Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Mar 01 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

So much fiction relies on what’s missing from a story, the details an author fails to or chooses not to include. In the spirit of just such incomplete information, Vladimir Nabokov’s 1962 novel Pale Fire delivers that most unreliable of narrators, the mad Charles Kinbote, who obsesses over ping-pong, young boys, and his beloved country of Zembla.

As Kinbote tries to convince his poet-neighbor John Shade to write an epic about this idyllic land overthrown by revolution, the reader is left to wonder what is up with Zembla. Is it just a metaphor for Nabokov’s pre-Revolutionary Russia? Is Zembla meant to be real inside the book, or is it only a figment of Kinbote’s delusional mind?

In “A Bolt from the Blue,” her early review of Pale Fire, Mary McCarthy noted the existence of a real-world Zemblan corollary in the Soviet Union: the twin Arctic islands of Nova Zembla. Perched above the continent on the border between Europe and Asia, the islands had come to represent, in both poetry and legend, the extreme, uncharted north.

In “A Bolt from the Blue,” her early review of Pale Fire, Mary McCarthy noted the existence of a real-world Zemblan corollary in the Soviet Union: the twin Arctic islands of Nova Zembla. Perched above the continent on the border between Europe and Asia, the islands had come to represent, in both poetry and legend, the extreme, uncharted north.

Key parts of The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov are devoted to exploring the connections between the two, which are many. But the links between a half-mythical Zembla and Nova Zembla have been considered before, in other contexts.

William Boyd, the man charged with generating the next installment in the James Bond saga, wrote a 1998 novel called Armadillo, which winks toward both Zembla and Nova Zembla. His tale of the strange events that befall insurance adjuster Lorimer Black add the word zemblanity to our literary lexicon.

389. Serendipity. From Serendip, a former name of Ceylon, now Sri Lanka. A word coined by Horace Walpole, who had invented it based on a folktale whose heroes were always making discoveries of things they were not in quest of. Ergo: serendipity, the faculty of making happy and unexpected discoveries by accident.

So what is the opposite of Serendip, a southern land of spice and warmth, lush greenery and hummingbirds, sea-washed, sunbasted? Think of another world in the far north, barren, icebound, cold, a world of flint and stone. Call it Zembla. Ergo: zemblanity, the opposite of serendipity, the faculty of making unhappy, unlucky, and expected discoveries by design.

Two years later in an “On Language” column for The New York Times, William Safire considered (then) recent U.S.-Russian nuclear proliferation talks, mentioning that “arms controllers know that the Russians have been setting off non-nuclear explosions at its nuclear test facility on the barren, frigid Arctic island of Nova Zembla.” Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Feb 25 2013

Filed In: News

More good news! With just over a week to go until The Secret History’s publication on March 6, Kirkus has given the book a starred review. Lots of generous things in there, most of which are still behind a paywall. But here’s a peek, skipping the spoilers (and there is one big spoiler, so don’t hunt down the review if you’re going to read the book):

Drawing on new biographical material and her sharp critical senses, Pitzer reveals the tightly woven subtext of the novels, always keen to shine a light where the deception is not obvious … a brilliant examination that adds to the understanding of an inspiring and enigmatic life.

With the book soon to arrive, I’m very much looking forward to getting out and doing readings—and hope to meet lots of you in person. Several upcoming dates have been added to the Events page. The current roster now includes the following:

A March 13 noon talk in New York City at the 92nd Street Y’s Tribeca location. There’s still room, so plan to play hooky from work just this once, and register today. Book signing to follow! This event is especially thrilling because Nabokov himself once did a reading for the 92nd Street Y. (More on this soon.)

The next day, March 14, we’ll have a reading/reception/book-signing/launch party in Washington, DC, in the beautiful new District building of NYU (yes, NYU in DC). Free, but you must register.

On March 29, I’ll be reading and signing books at Harvard Book Store in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This stop has the added bonus of being in the heart of Nabokov’s 1940s stomping grounds. Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Feb 20 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

Born in the nineteenth century, was literary alchemist Vladimir Nabokov also a digital pioneer for our electronic era?

Nabokov’s description of a primordial emoticon from 1969 (“I often think there should exist a special typographical sign for a smile—some sort of concave mark, a supine round bracket”*) gets new coverage each decade from those chronicling the history of pictographic punctuation.

But some are taking the idea of Nabokov as a pioneer a little more seriously. Simon Rowberry, a research student at Britain’s University of Winchester, is exploring Nabokov’s 1962 novel Pale Fire as a forerunner of hypertext. (Hypertext is a digital story in which parts of the text link explicitly to other sections, allowing readers to navigate within the story to create various versions of the text.)

Pale Fire is presented by demented narrator Charles Kinbote as a 999-line poem which he is annotating in the commentary that forms the bulk of the book. The novel has a storyline that progresses during sections of the foreword and commentary, but the reader is often directed back to lines from the poem or sent to other annotations (“see also note to line 894”). Subtler elements of the story emerge only through cross-references.

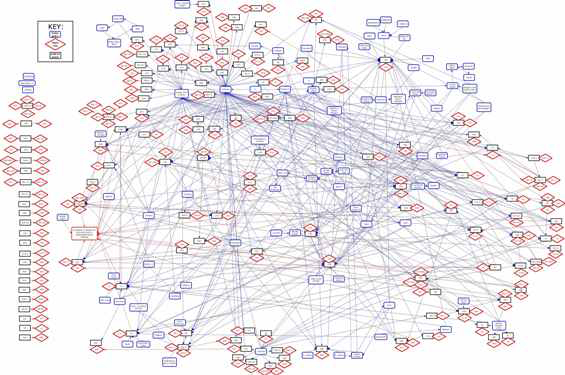

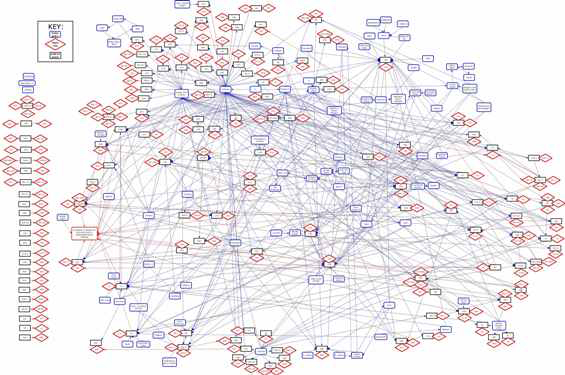

In this extraordinary graphic from a poster presentation given two years ago at the ACM Hypertext Conference in the Netherlands, we can see how Rowberry has begun to chart Pale Fire’s internal links and loops. Click the image to see an expanded version—it should then be zoomable for detailed viewing.

The novel’s principal characters—John Shade, Kinbote, and Jakob Gradus—sit in a horizontal row of blue boxes in the top third of the graphic.

The word hypertext dates back to 1963, just a year after Pale Fire’s publication—and the two were linked early on. IT trailblazer Ted Nelson, who coined the term, reportedly got permission to use Pale Fire in a 1969 hypertext demo at a conference hosted by Brown University.

Rowberry is working on his dissertation, “The Literary Web,” which will include a chapter on Pale Fire and hypertext. This week he suggested that examining Pale Fire as hypertext is more than an exercise in revisiting history: Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Feb 15 2013

Filed In: News

Just two quick news items before the weekend. I’m thrilled to share that Booklist, the American Library Association’s magazine, has given The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov a starred review. Here’s the closing paragraph from their very generous comments:

Through her historically grounded readings of [Nabokov’s] fiction, Pitzer discredits the widespread but misleading perception of Nabokov as an art-for-art’s-sake writer indifferent to the moral and political exigencies of his day. But as readers explore his devious strategies for veiling sobering historical realities in aesthetic illusions, they slowly become aware of the interpretive responsibilities that Nabokov places on the reader. A penetrating analysis certain to compel a major reassessment of the Nabokov canon.

Please also note that The Secret History‘s publication date has been moved up a full week, to Wednesday, March 6th. We’re working on putting together a launch event in New York City that night. Post a note in comments or email me if you want to know details once they’re set.

But a relentless search for links like these sometimes doesn’t lead to any greater understanding of what a writer has accomplished—after all, the magic is in the transformation. I, too, might look down on that same tree, but I can’t write Bend Sinister, let alone Lolita.

But a relentless search for links like these sometimes doesn’t lead to any greater understanding of what a writer has accomplished—after all, the magic is in the transformation. I, too, might look down on that same tree, but I can’t write Bend Sinister, let alone Lolita. In “A Bolt from the Blue,” her early review of Pale Fire, Mary McCarthy noted the existence of a real-world Zemblan corollary in the Soviet Union: the twin Arctic islands of Nova Zembla. Perched above the continent on the border between Europe and Asia, the islands had come to represent, in both poetry and legend, the extreme, uncharted north.

In “A Bolt from the Blue,” her early review of Pale Fire, Mary McCarthy noted the existence of a real-world Zemblan corollary in the Soviet Union: the twin Arctic islands of Nova Zembla. Perched above the continent on the border between Europe and Asia, the islands had come to represent, in both poetry and legend, the extreme, uncharted north.