posted by Andrea Pitzer on Apr 23 2013

Filed In: Beginner

When is Vladimir Nabokov’s birthday anyway? Depending on where you look, you’ll see April 10, April 22, and April 23 listed, but which is it?

The answer is… all three. As Nabokov explains in his autobiography, Speak, Memory, he was born in Russia in 1899 on April 10, but at that point in time Russia was still using the Julian calendar, rather than the Gregorian calendar in place in the West. April 10, 1899 under the Julian calendar in Russia was the same day as April 22, 1899 in much of Western Europe and America. April 10, 1899 would be Nabokov’s “Old Style” birthday, and April 22, his birth date in the “New Style.”

After the Revolution, Russia joined the West in adopting the Gregorian calendar, which left émigrés using both systems for a few years. Rul, the newspaper Nabokov’s father edited in Berlin, for example, continued to use Old and New Style dates for several years.

So where does April 23 come from? Well, celebrating a day later allowed Nabokov to distance himself from Vladimir Lenin (born Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov), who also arrived in the world on April 10/April 22, nearly three decades before Nabokov’s birth. But another quirk of the conversion from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar was that the Julian calendar had certain leap days that the Gregorian calendar dropped.

So while the difference between the two calendars was twelve days in 1899, in 1900, the gap expanded one additional day, to 13 days. April 10, 1899 converts to April 22, 1899, but by the following year April 10 became April 23. Nabokov was born on April 22, but celebrated his first birthday on April 23, which was, according to the Gregorian calendar, the day he turned one.

Enough about birthdays. What about declassified FBI files?

Nabokov and the FBI

Readers of The Secret History will know how caught up the Nabokovs’ family members were in intrigue, espionage, and intelligence matters, from the murky days of vague diplomatic missions, polyglot tendencies, and code-breaking skills of Nabokov’s uncle Ruka in pre-Revolutionary Russia to other relations’ clearer links with US Army Intelligence and CIA anti-Communist efforts decades later.

After the war, Nabokov had tried to get a State Department job that ended up going to his cousin Nicholas. For most of the first decade of the Cold War, he taught at Cornell University, where his direct involvement with US-Soviet political turmoil consisted of befriending the FBI agent tasked with keeping an eye on the campus. (During these years, then-Vice-President Richard Nixon requested an investigation into communism at American colleges and universities, and the FBI created a series of reports on individual schools, charting the degree to which they believed communist elements had infiltrated each institution.)

But as a Russian émigré in an era in which Russians had become suspect, did Nabokov merit investigation by the FBI? Did the FBI have anything on Nabokov?

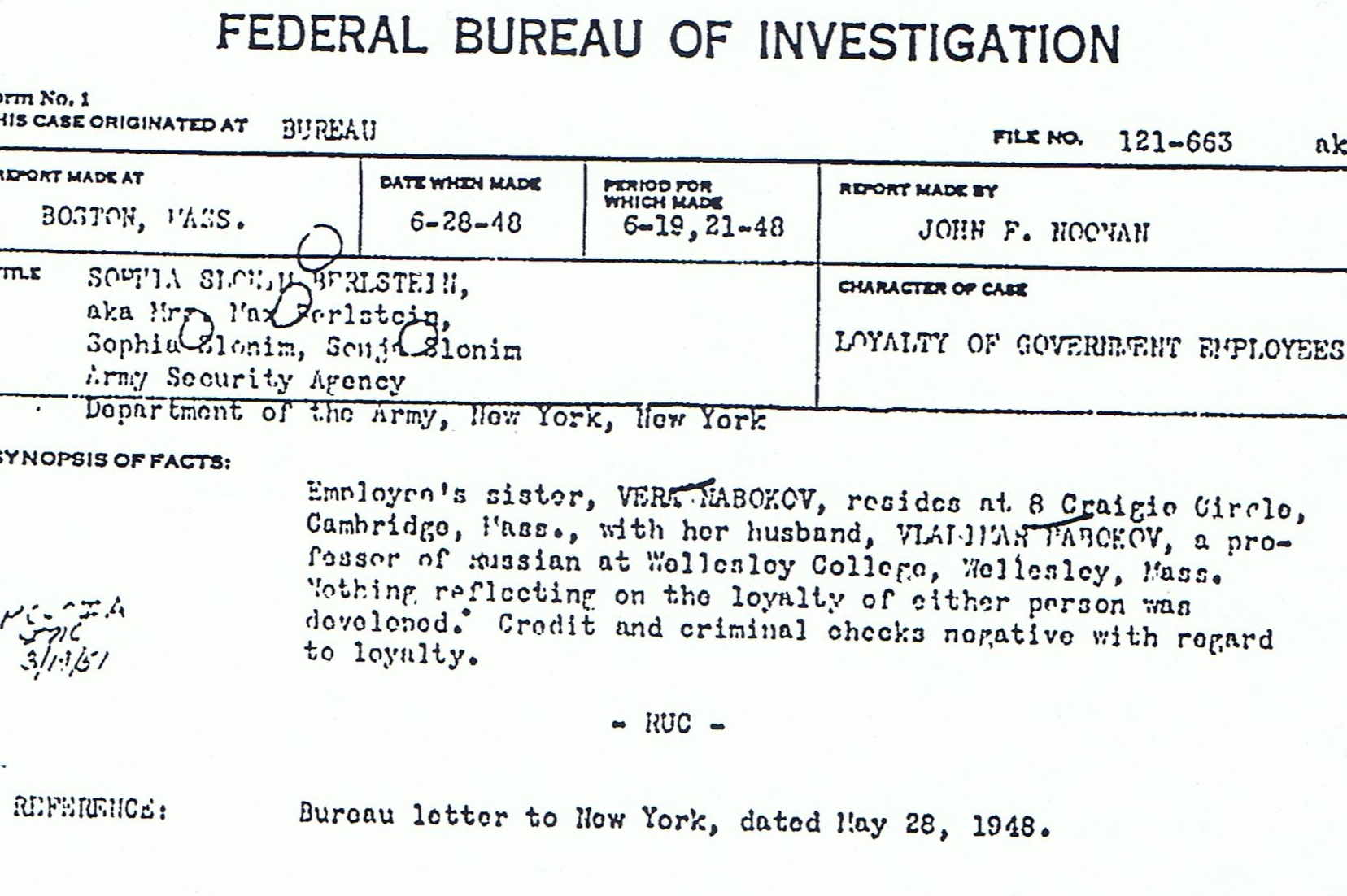

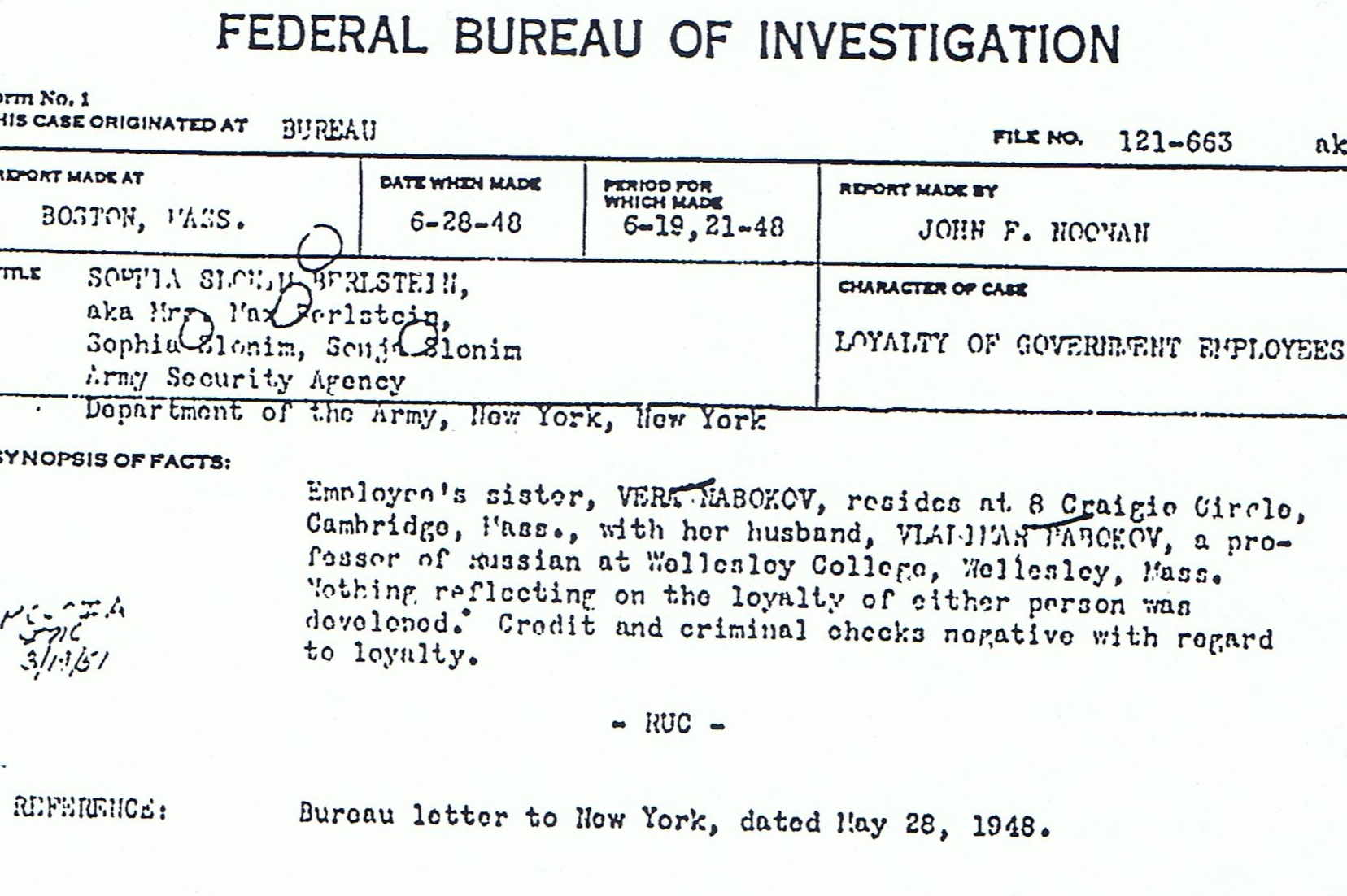

The only FBI files on Vladimir Nabokov divulged to date are very thin and come not from any investigation centered on him, but one focused on Sonia Slonim, the younger sister of his wife Véra.

Sonia had dabbled in intrigue during the war, and her FBI file is extensive. I’ll write more on her later, but for now, suffice it to say that an international loyalty investigation on Sonia in 1948 caused agents to visit Vladimir and Véra Nabokov, then still in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The investigators ended up submitting three less-than-full pages on the couple, which were summarized in a fourth. Here’s a detail from the summary page looking into “VLADIMAR” and VERA NABOKOV (click each image to see the full page):

Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Apr 17 2013

Filed In: News

In case you missed it, last week I got a chance to talk about The Secret History with Marco Werman, host of Public Radio International’s “The World.”

We discussed Nabokov’s gift for outrunning history, 20th-century anti-Semitism, and Solzhenitsyn, among other things. At one point, Werman asked about the reception the book is getting, and I somehow ended up referencing Depeche Mode.

Werman: Yeah. I’m interested to know what critics have been saying to you about this book because so many people see Nabokov strictly, as you write, to “art for art’s sake”. Leave the back story out. What do you think about that and what have you heard?

Pitzer: It can be tricky because I think everybody, critics, scholars, general readers, have their own Nabokov. It’s like your own personal Jesus. They have their own Nabokov and some have felt that looking this closely at history is somehow to tie these stories down or to strip them of their magic in some way. And I would agree that if you just reduced his works to nothing but a series of chronological illusions, that would definitely be flattening the novels out. But I think to ignore this history that’s embedded in the books is really to miss half the story.

I’m not so much interested in revisiting “Personal Jesus” as I am underlining why this history matters. Nabokov’s writing has generated a plethora of books and essays exploring the literary allusions buried in his work and what they mean for the stories he was telling. It’s my hope that The Secret History complements all that fabulous spelunking by doing the same thing with Nabokov’s historical allusions.

You can hear the whole PRI interview, as well as listen to me read an excerpt from the first chapter of the book, here.

In other news, I recently weighed in on a Nabokov/Great Gatsby literary hoax for David Haglund over at Slate and got a nice shout-out in the Los Angeles Times from writing guru and biographer Ben Yagoda. And the Midwest Book Review wrote up The Secret History, calling it a “seminal work of painstaking research and scholarship.”

More soon on upcoming readings in the Midwest and on the West Coast.

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Apr 12 2013

Filed In: Beginner

[The first in a series of guest posts on Nabokov and history.]

When I first heard about the forthcoming publication of The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, I pre-ordered the Kindle version immediately. I was hugely curious about the book, as I humbly thought I knew pretty much everything there was to know about Nabokov’s history. I had worked during the 1970s at Ardis Publishers, a publisher of Russian literature that dealt regularly with the Nabokovs during my time there, and had seen a secret side to Vladimir and Véra that was viewable only to those of us at Ardis.

I started reading with a smug air, and ended up surprised by the book’s revelations. The careful tracing in The Secret History of concentration-camp and anti-Semitism themes running (often cryptically) throughout Nabokov’s life and novels furnishes proof of the author’s deep political engagement—a stance concealed brilliantly by the public pose he struck during his life as an artist who resolutely disdained the political. More to my point here, the revelations brought back vivid memories of the quiet, kind-hearted political engagement we at Ardis regularly witnessed in the Nabokovs.

So The Secret History managed the paradoxical trick of both surprising me and confirming what I already knew.

Ardis Publishers (the name comes from the name of the country estate in Nabokov’s Ada) was founded by Carl and Ellendea Proffer in 1971. At that time, Carl was a leading Nabokov scholar and perhaps the west’s foremost authority on contemporary Soviet literature. The Nabokovs greatly admired his Keys to Lolita, which remains, in my view, the best exploration of the ingenious (and ingeniously misleading) system of literary allusions and their meaning in that brilliant novel.

The mission at Ardis was threefold: to publish, in Russian and English, the work of suppressed contemporary Russian writers and poets who could not publish in the Soviet Union; to reissue classic works of 20th-century fiction and poetry that had been censored out of existence in the Soviet Union, and to smuggle these editions back into the USSR; and to promote, in the western world, purely literary suppressed Soviet writers, as opposed to those, like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who were famous in the west for largely political reasons. There was a rather large number of gifted Soviet literary figures who couldn’t garner much interest in the west unless they were also political figures.

So we had an intense sense of mission at Ardis—one considerably heightened by the cloak-and-dagger nature of a lot of our work. Our reissued Russian-language books by some of the greatest Russian writers of the century (Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, Marina Tsvetaeva, Nikolai Gumilev) were printed in little pocket-sized editions that were easily smuggled. “Companies” with such murky names as “International Literary Associates” would buy hundreds, sometimes thousands of copies at a time; we always suspected, but never knew for sure, that they were CIA fronts. Read more ›

Tags: Andrei Bitov, Anna Akhmatova, Ardis Publishers, Carl Proffer, Ellendea Proffer, Fred Moody, Joseph Brodsky, Lev Kopelev, Marina Tsvetaeva, Nikolai Gumilev, Osip Mandelstam, Raisa Orlova, Sergei Dovlatov, Vasily Aksenov, Viktor Erofeev, Vladimir Nabokov

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Apr 08 2013

Filed In: News

What do Entertainment Weekly, The Brooklyn Rail, and the Netherlands’ Radio One all have in common?

They’ve been pondering Nabokov!

Writing about Mad Men‘s season premiere, EW‘s Keith Staskiewicz begins with a quote from Nabokov (which, he notes, comes from the era in which the episode is set). The two sentences he includes are taken from the opening paragraph of Speak, Memory and talk about the twin abysses, “two eternities of darkness,” that lurk before birth and after death. For those wishing to further contemplate mortality—Don Draper’s or their own— Staskiewicz recaps the episode and addresses the Nabokovian implications.

The Brooklyn Rail also recently considered Nabokov, but in this case, it was The Secret History that got the spotlight. Reviewer Christopher Michel called the book’s research “astounding” and noted that when it comes to Nabokov making use of political history:

It’s possible that for Nabokov the human and the minute were the political—that the forgotten details of yesterday’s headlines (and the lifelong effects they had on survivors) held far more significance for him than the broad brushstrokes of history held in the popular imagination. It’s possible that for Nabokov, the problem with sweeping histories and clashing ideologies lay, finally, in that very loss of detail: the oversimplifications and generalizations that ideology necessarily entails. His works were careful, precise, and detailed because he was trying to create (or find) the kind of people who could be careful enough readers to understand the adverse effect those generalities have on the mind, and to resist them. If so, Ms. Pitzer is one of those readers. And she has done us all a great service in revealing more of Nabokov’s genius than was previously known. This book is a vital aid to any fan of Nabokov’s who wants to understand a little more clearly what the stakes really are.

And additional kudos came on Saturday when novelist and critic Arie Storm talked in depth about The Secret History on Radio One in the Netherlands. Recommending the book to listeners as “a phenomenal read,” he called it the book of the month.* Dutch speakers can listen to the whole program here.

If you include the publication of Nabokov’s Selected Poems and The Tragedy of Mister Morn (both shepherded ably into print in the last year by Thomas Karshan), and the forthcoming Letters to Vera (perpetually delayed but now apparently slated for February 2014), The Secret History is arriving with a wave of other information about Nabokov’s life and work.

So much newly-public or newly-collected material brings to mind the words of Faulkner (whose writing Nabokov insulted): “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” As we reconsider Nabokov’s work, I will note that Mad Men, like The Secret History, nods to the ongoing play between a character’s hidden history and the harm he sets in motion in daily life.

*Thanks to Laurens Nijzink for the unofficial translation.

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Apr 04 2013

Filed In: Beginner

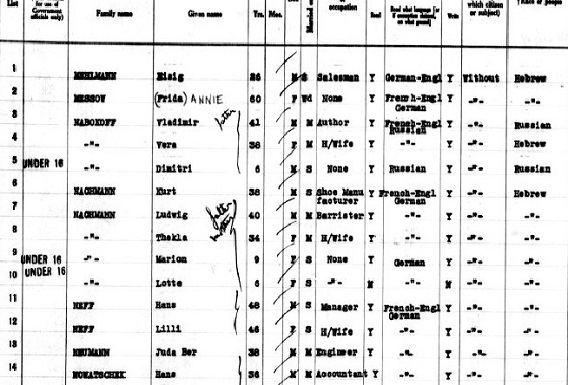

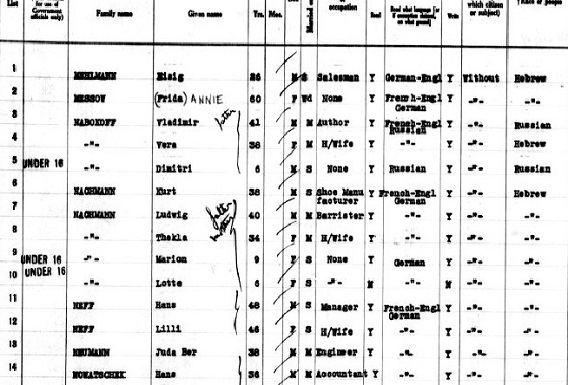

When Vladimir Nabokov crossed from Europe to America on the SS Champlain in May 1940, he was accompanied by his wife Véra and son Dmitri. I’ve already posted Vladimir’s and Véra’s immigration files. Today I want to share the ship’s passenger record for their trip on the Champlain.

In a detail from the first of two pages (click the image to see the full page), the Nabokovs are the third, fourth, and fifth passengers listed. In what was standard practice at the time, you can see that Vladimir is listed as Russian, Véra as Hebrew, and Dmitri as Russian.

It was fortunate for Véra and Dmitri that the Nabokovs escaped that month, as France would fall to the Nazis just three weeks after their departure, and foreign Jews in Occupied France would soon face harrowing fates. Arrested and detained in French-run concentration camps that served as transit stations, they and their children would eventually be deported eastward.

One thing that surprised me during my research was that French laws during the Occupation in some cases went further than German laws. In Germany, Véra alone had been classified as Jewish, having three or more Jewish grandparents. But after new laws were imposed in Occupied France, Dmitri’s fully-Jewish mother alone would be enough to legally identify him as a Jew.

The French police set up no death camps. But during the war, the police did gather or collaborate in gathering approximately 75,000 Jewish residents into transit camps and then deported these prisoners to their deaths, principally at Auschwitz-Birkenau or Sobibor. Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Mar 28 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

Russian author Isaac Babel is reported to have said of his literary contemporary Vladimir Nabokov that “he can write, but he’s got nothing to say.” Early in his career, Babel wrote a short story just three pages long called “Line and Color.” This story goes to the heart of the tension between invention and reality in art, and oddly enough, also explains how it is that readers like Babel have missed part of what Nabokov was up to.

Born five years apart in pre-Revolutionary Russia, Babel and Nabokov both became extraordinary stylists. Their fiction was condemned as obscene. Nabokov was known for his escapes, both literary and literal. Babel, also celebrated for his vivid, poetic images, found his luck less dependable in the real world.

Babel’s experiences in the First World War and then the Russian Civil War spurred the the creation of his first timeless characters in legendary stories that made his name, even as they made him enemies. He found recognition and built a place for himself in the early Soviet literary establishment, but it was for many reasons a precarious situation.

Trotsky and Kerensky

Babel’s “Line and Color” pulls in two real-world characters—Alexander Kerensky and Leon Trotsky—who also appear in The Secret History. The story recounts a meeting between the narrator and Kerensky in December 1916, just two months before revolution would force the Tsar to abdicate. In the real world, in the months following the time and place in which the story is set, Kerensky rose to become a Minister and then, eventually, Prime Minister in the series of Provisional Governments that briefly ruled Russia before the Bolshevik takeover in October 1917.*

In Babel’s story, the narrator has a meal with Kerensky just outside Helsinki, Finland. The description of the meal is concise but charged with images of decadence and collapse. Just after a sighting a beautiful countess who recalls Marie Antoinette, the narrator watches Kerensky eat three pieces of cake. Read more ›