Nabokov’s wartime escape on the SS Champlain

When Vladimir Nabokov crossed from Europe to America on the SS Champlain in May 1940, he was accompanied by his wife Véra and son Dmitri. I’ve already posted Vladimir’s and Véra’s immigration files. Today I want to share the ship’s passenger record for their trip on the Champlain.

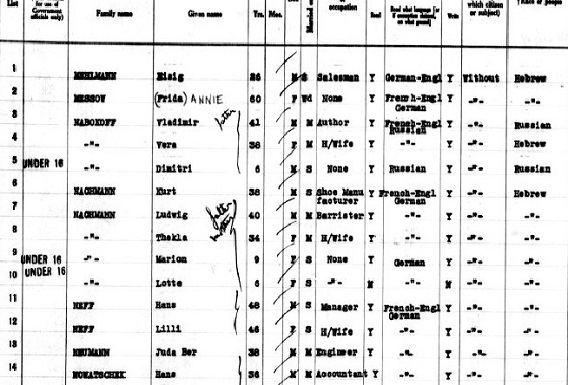

In a detail from the first of two pages (click the image to see the full page), the Nabokovs are the third, fourth, and fifth passengers listed. In what was standard practice at the time, you can see that Vladimir is listed as Russian, Véra as Hebrew, and Dmitri as Russian.

It was fortunate for Véra and Dmitri that the Nabokovs escaped that month, as France would fall to the Nazis just three weeks after their departure, and foreign Jews in Occupied France would soon face harrowing fates. Arrested and detained in French-run concentration camps that served as transit stations, they and their children would eventually be deported eastward.

One thing that surprised me during my research was that French laws during the Occupation in some cases went further than German laws. In Germany, Véra alone had been classified as Jewish, having three or more Jewish grandparents. But after new laws were imposed in Occupied France, Dmitri’s fully-Jewish mother alone would be enough to legally identify him as a Jew.

The French police set up no death camps. But during the war, the police did gather or collaborate in gathering approximately 75,000 Jewish residents into transit camps and then deported these prisoners to their deaths, principally at Auschwitz-Birkenau or Sobibor.

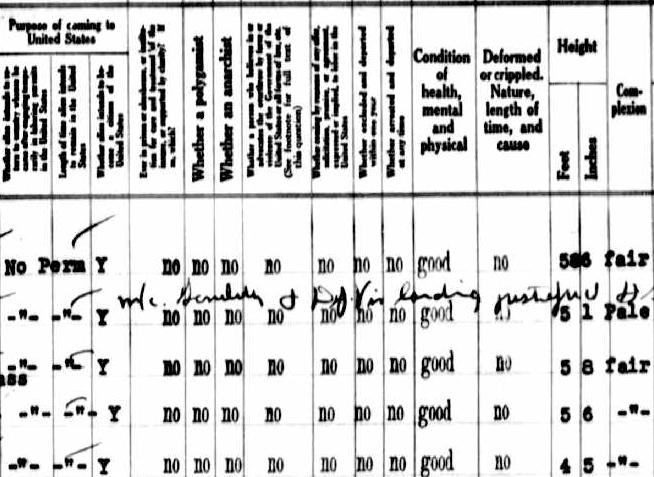

This detail from page two of the record of the Nabokovs’ voyage to America shows some of the questions that were asked of immigrants, including any tendencies toward polygamy or anarchy. (Click the image to see the full page in zoomable form.) Passengers had to have a contact in the U.S., and things like defective speech, senility, or poor vision had to be noted and an exemption made in order for afflicted passengers to be allowed into the country. Each condition was recorded, and where entry was granted despite it, “landing justified” was written in, followed by the initials of the evaluator.

The Champlain had been chartered for the evacuation of Jewish refugees, and the Nabokovs and their shipmates were the last immigrants it would deliver to America. On its return voyage, the ship struck a German mine, which killed 11 crew members and effectively sank it. Days later, it was hit by a German torpedo and rendered irretrievable.

[On page two, the height given in these records for Vladimir Nabokov is likely incorrect. See “Vladimir Nabokov’s immigration file” for details.]

Microfilm images courtesy the U.S. National Archives