Was Véra Nabokov’s sister a spy?

When the Nabokovs came to America in 1940, they sailed through immigration, pausing only to struggle with a locked trunk that needed to be inspected by customs. But arrival in a new country was less simple for thousands of other refugees fleeing Europe during World War II, including Véra Nabokov’s younger sister Sonia. Making her way to New York just eight months after the Nabokovs’ entry, Sonia’s relationship with US government agencies would be both deeper and more complex.

Sonia Sophia Slonim had been born in St. Petersburg six years after Véra. In the wake of the Revolution, she fled her homeland with her sisters along a risky route at the age of 10.

Sonia Sophia Slonim had been born in St. Petersburg six years after Véra. In the wake of the Revolution, she fled her homeland with her sisters along a risky route at the age of 10.

Living in Berlin for several years, she studied acting at the highly-respected Hoeflich-Gruening School of Drama as a teen, then went to work in the German offices of the perfume companies Houbigant and Cheramy. (This may have provided some small inspiration later for Humbert Humbert’s own brief career in perfumes in New York.)

Moving to Paris long before the Nabokovs, she worked translating film scripts for such masters of cinema as Max Ophüls. In America she would tell friends that in the decade before the war began, she had spent several years working with French intelligence. She was certainly mixed up in intelligence matters, though I was unable to find any hard evidence of a role as an agent for the French (which does not mean that she was not).

A French spy? A German spy?

Due to a romantic relationship with a German man also in Paris (more on him and their time together later this week), Sonia Slonim stayed in the city until hours before Hitler’s forces invaded. At the last minute, the couple ended up fleeing to Casablanca, eventually making their way to America in January 1941.

Also probably due to her romance, when Sonia’s ship crossed the Atlantic, someone relayed a cable from French facilities at Martinique to U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull, suggesting that Slonim should be “observed due to unofficial reports here that she may be a German spy.” Sonia was not detained at Ellis Island, but her mail was watched for a period of time, until it was determined that she was not a threat. Having listed Véra’s latest West Eighty-seventh Street address as her destination on arrival, Sonia soon got an apartment not far away from the Nabokovs, and began teaching at the International School of Languages.

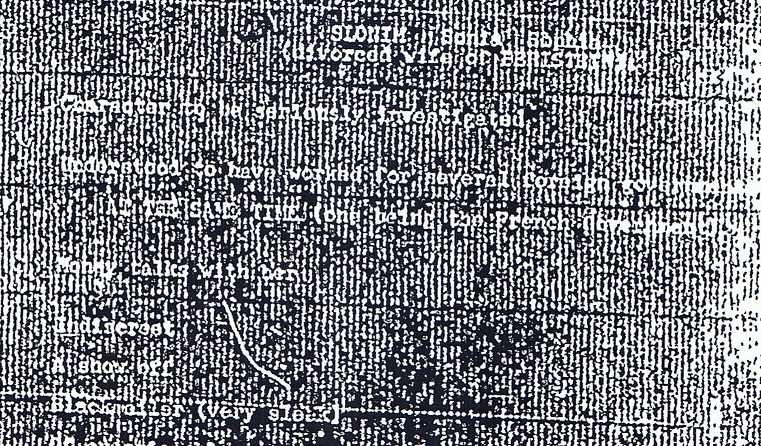

But her past would return to haunt her after the war, when she went to work for the US Army Security Agency as a cryptographer. During a routine security clearance, someone (presumably a reference who had been contacted by agents conducting the background investigation) wrote an anonymous letter to the lieutenant colonel in charge, saying that Sonia Slonim had a character that should be “seriously investigated,” that she was “understood to have worked for several foreign governments AT THE SAME TIME” [sic], that she was “Indiscreet,” “A show off,” and a “blackmailer” of the “very sleek” variety. A broader investigation was launched, turning up the wartime accusation of being a German spy. Here’s a close-up of part of the letter (click to see the full-page image).

The FBI got involved. Informants and acquaintances were interviewed in Germany, France, California, New York, Virginia, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Véra and Vladimir Nabokov were briefly investigated because of their connection to her. Sonia had spent several months in Hollywood and worked again with Max Ophüls, who had also fled France for America. Her association with Jewish filmmakers and some political radicals involved with Free French newspapers (who were already the subjects of separate investigations) were likewise noted. Reflecting the government’s preoccupation with Jewishness as a marker for political identity, it was said by one (incorrect) informant that she had been born with the last name Levin but had changed it to Slonim to hide her Jewish roots.

In the end, nothing concrete could be found against Slonim, who appears to have never been a German spy or to have worked against American interests in any way. But her associations—and her claims to friends about intelligence work for France that she never reported to the Army Security Agency when she went to work for them—left her in a gray area. The international loyalty investigation dragged on and on without clearing her. Eventually she left her position in Arlington, Virginia and returned to New York, where she became a translator for the United Nations.

Slonim is just one of Nabokov’s family members who entered–or were caught up in–the intrigue of their century. In my next post, I’ll look at her longtime German boyfriend, and how their relationship (and fragments of his story) appear to have made their way into Nabokov’s art.