Beautiful failures: Nabokov, Stalin, and the death of Hamlet

Stuck in the shadows of more accomplished, more loved siblings, lesser novels are often the bitter children of genius. They surrender family secrets and the details of their creators’ flawed parenting. Their failures provide their own intrigue.

Such is the case with Bend Sinister, Vladimir Nabokov’s first novel written after his 1940 arrival in America. Revealing more authorial struggles than triumphs, the novel recounts the fate of a freethinking philosopher in a totalitarian state. Filled with echoes of “Lenin’s speeches, and a chunk of the Soviet constitution, and gobs of Nazist pseudo-efficiency,” the book lurches from horror to slapstick and back, grinding gears as it goes.

Such is the case with Bend Sinister, Vladimir Nabokov’s first novel written after his 1940 arrival in America. Revealing more authorial struggles than triumphs, the novel recounts the fate of a freethinking philosopher in a totalitarian state. Filled with echoes of “Lenin’s speeches, and a chunk of the Soviet constitution, and gobs of Nazist pseudo-efficiency,” the book lurches from horror to slapstick and back, grinding gears as it goes.

A chapter at the center of the story records a translator’s struggles with a state-sponsored, monstrous version of Hamlet. In his June 1960 review of the novel for Encounter, Frank Kermode criticized the Hamlet episode as a “digression” and “a useless but agreeable exercise of intellect.” The polyglot gamesmanship of the chapter fails to integrate the warped play into the stillborn society.

Yet the fate of Hamlet in a police state was not some abstract question, and the play’s the thing that links Nabokov’s fictional universe with our world in a haunting way. Just before Nabokov began work on his novel in 1941, Joseph Stalin criticized Hamlet, triggering its disappearance from Soviet stages for more than a decade. During this silence, Bend Sinister carried the wreckage of the play, standing as a condemnation of art stripped down to politics. In the process, Nabokov’s book indirectly memorialized a titan of Russian theater.

Hamlet in Russia

Shakespeare ranked as one of Nabokov’s three favorite writers (the others: himself and Pushkin), and the Bard’s plays make an appearance in more than one book by Nabokov, including the novel Pale Fire, whose title was provided by Timon of Athens and perhaps even by Hamlet itself. From the nineteenth century through the twentieth, Russians loved Shakespeare. Analyzed by the revolutionary Decembrists, the historical tragedies played a pivotal role in Alexander Pushkin’s ascent to literary immortality. As Siggy Frank notes, Nabokov particularly revered “the prodigious beauty” of Hamlet, calling it “probably the greatest miracle in all of literature.”

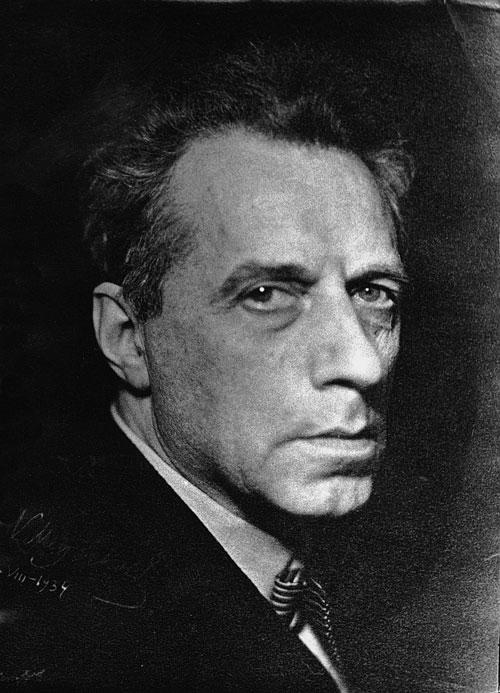

Constantin Stanislavsky and Gordon Craig staged a landmark Russian production of that play beginning in 1911. Their collaboration for the Moscow Art Theater revolutionized drama across Europe, inspiring veteran director Vsevolod Meyerhold—already a legend for his work in theater, opera, and cinema—to likewise try his hand at staging Hamlet.

Meyerhold’s first attempts began as early as 1915 but did not bear fruit. Pressured to alter his work under Tsarist rule, he cheered the Revolution and joined the Communists, dreaming that the arts might flourish under Soviet rule. But he soon found himself criticized on the pages of Pravda by revolutionary leader Nadezhda Krupskaya, wife of Vladimir Lenin.

Meyerhold’s first attempts began as early as 1915 but did not bear fruit. Pressured to alter his work under Tsarist rule, he cheered the Revolution and joined the Communists, dreaming that the arts might flourish under Soviet rule. But he soon found himself criticized on the pages of Pravda by revolutionary leader Nadezhda Krupskaya, wife of Vladimir Lenin.

He was eventually relieved of his position and chastised for “excessive radicalism.” As the decade wore on, he continued to struggle with Hamlet. He did not want to cut a line but could not find a way to leave it intact and stage it to his standards.

After Lenin’s death in 1924, Stalin rose to power. Meyerhold’s reputation continued to grow, and despite the censors, he managed to carry out extraordinary work, including productions of Chekhov and Tchaikovsky. But still there was no Hamlet.

He planned a book about how to stage the play (Hamlet: The Story of a Director), which would wrestle with its questions. He imagined a theater devoted only to various productions of Hamlet.

The Great Purge began. Surviving despite his precarious situation, Meyerhold was removed in 1938 from the theater he had founded. Sheltered by Stanislavsky for a time, he was picked up by Soviet secret police in June of 1939—an event reported internationally in newspapers. Reports of the arrest of Meyerhold’s wife appeared the following month.

Taken in for interrogation, tortured, and forced to confess to anti-government activity, he recanted his confession at trial but was convicted. He was shot on February 2, 1940.

Nabokov had attended and been impressed by Meyerhold’s Berlin production of The Government Inspector a decade before, but neither Nabokov nor the world would see the realization of his vision for Hamlet. Months after Meyerhold’s death, however, the Moscow Art Theater, which had hosted Stanislavsky’s hallmark production nearly 30 years before, began rehearsing the play.

The following year Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, who had designed stage sets for Meyerhold and been Nabokov’s art tutor in childhood, collaborated on the production of Nabokov’s play The Event in New York.

Hamlet and Stalin

As Shakespeare’s longest work, Hamlet has as many interpretations as it does words, several of which wrestle with the anxiety of the self in the world. In Nabokov’s invented totalitarian state, however, the plotline is distorted to nod to Nazi mythology. The doubting Hamlet is diminished to favor a more “healthy, vigorous and clearcut Nordic theme,” in which the decisive prince, Fortinbras, seeks to reclaim ancestral lands.

When Stalin turned his attention directly to Hamlet, however, he did not try to warp it to fit a more Soviet vision. Instead, as Arthur Mendel explains in “Hamlet and Soviet Humanism,”

an offhand remark by Stalin in the spring of 1941 questioning the performance of Hamlet at that time by the Moscow Arts Theater was sufficient to end rehearsals and to postpone the performance indefinitely. In the following years, the very idea of showing on the stage a thoughtful, reflective hero who took nothing on faith, who scrutinized intently the life around him in an effort to discover for himself, without outside “prompting,” the reasons for its defects, separating truth from falsehood, the very idea seemed almost “criminal.”

Stalin’s comment launched a 12-year moratorium. Only his death in 1953 liberated Hamlet.

Amid the loosened censorship that followed, critics debated how to stage the play. It was Shakespeare, it was Hamlet, and yet it also had another face for Soviet dramatists—the demand on the individual to recognize evil and act within history to counter it. A fever for Hamlet gripped the country, and the play became a key conduit by which the country struggled to free itself from Stalin’s legacy. Looking back, Mendel asks,

Can there be any doubt in the light of these quotations that the Soviet critics were practicing what, through Hamlet, they preached? They were speaking out against their own Elsinore in the only speech that tyranny permits, tongue-tied speech, the Aesopian language of literary criticism, traditional among the Russian intelligentsia, that ostensibly talks about other places and other times when the real subject is clearly here and now.

Likewise using the canvas of art to enfold epic history, Nabokov’s Bend Sinister made its way to a British publishing house in 1960. So it happened that a Russian-born naturalized American who revered the unsullied Hamlet as the highest pinnacle of literature unleashed a totalitarian version of the play on the world once more, just at the moment when Shakespeare’s original could be performed again in Soviet Russia.

In the end, Nabokov’s unsuccessful attempt to frame his novel as a tongue-tied play within a farce found its parallel in Meyerhold. Meyerhold never managed to fulfill his dream but similarly wondered if contorted interpretations should be dumped in order to look at “the tragedy of Hamlet as a play in which the tears are glimpsed through a series of traditional theatrical pranks.”

The reappearance of Hamlet and the preservation of Meyerhold’s ideas about it couldn’t reverse the truncation of his artistic vision or undo his death. As for the twin dismemberment of art and the individual that Nabokov depicted in Bend Sinister, Russia paid both prices for decades. Meyerhold paid them permanently. “Engrave on my tombstone,” he told his friends, “‘Here lies an actor who never played and never staged Hamlet.’”

[Addendum giving credit where credit is due: after this post went up, I unearthed a New Yorker article also called “Beautiful failures” that looked at early work from both Flaubert and Nabokov. Kudos to the New Yorker for coming up with the pairing first, and for an article worth reading.]

Images: Bend Sinister (top) and Vsevolod Meyehold (bottom).

To read more on Meyerhold’s career, visit the site of the Meyerhold Theater Center.