posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jan 25 2013

Filed In: Beginner

When most people think of the Russian Revolution, they think of 1917, the fall of the Romanovs, and the Bolshevik takeover. But before that Revolution (which was actually two revolutions, months apart), there was another one. More than a year into a disastrous war with Japan, and after months of strikes and bitterness over protesters killed in the streets, Tsar Nicholas II was forced in 1905 to make concessions to the people he ruled.

Plans were made to hold elections for a parliamentary-style congress, to be called the Duma. Many revolutionary parties scoffed at the idea of the Duma and boycotted the election. But Nabokov’s father, who was not a revolutionary, ran as a member of the progressive Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets) and was elected.

The Kadets controlled the First Duma in coalition with the Trudoviks, a moderate group of socialist revolutionaries. The possibilities for partnership began to sour quickly, with disagreements over land reform and Trudovik resentment of Kadet dominance in the new body. But for a time, they did manage to collaborate on legislation. An eloquent speech from V.D. Nabokov against the death penalty led to the passage of a measure outlawing it. Other steps were proposed to relieve famine conditions.

Nabokov’s father also gave a memorable speech arguing that the power of the Tsar and his ministers must be subordinate to that of elected lawmakers. The government did not agree, and the First Duma, a beacon of possibility for Russian democracy, was dissolved.

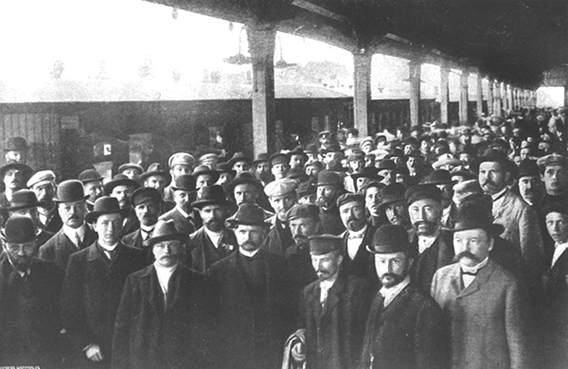

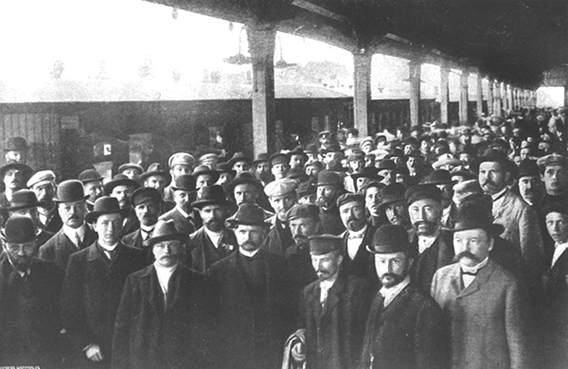

The decision stunned the legislators. The next day approximately 200 of the chamber’s deputies, mostly Kadets and Trudoviks, took a train across the Finnish border to Vyborg and put together a manifesto calling on Russians not to serve in the army or pay taxes. The image below was taken by photographer Karl Bulla, who traveled from St. Petersburg in the summer of 1906 to capture the moment.

I love all the hats in the picture—the dark homburgs and paler fedoras, the workers’ flat caps and the Swedish model not yet adopted by Lenin, all gathered together. A man in what appears to be a driver’s cap stands in the front, glancing down, while in the second row at the bottom left, V.D. Nabokov stares into the camera, exquisitely dressed in a tie and bowler, looking dismayed. As well he should—every deputy who had signed the manifesto was later put on trial, and most were sent to prison, including Nabokov’s father. Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jan 21 2013

Filed In: News

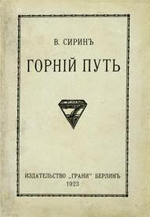

Before he wrote Lolita, before he came to America, before he met his wife Véra, Vladimir Nabokov was first and foremost a poet. And now the poetic at heart with four-figure pocket change might just be able to acquire a first edition of Gornii put (The Empyrean Path), a collection of Nabokov’s early poetry published in 1923 under the pseudonym Sirin.

Gornii put appeared less than a year after the death of Nabokov’s father, who helped prepare it for publication. (V.D. Nabokov was shot in March 1922 attempting to foil a political assassination in Berlin.)

Gornii put appeared less than a year after the death of Nabokov’s father, who helped prepare it for publication. (V.D. Nabokov was shot in March 1922 attempting to foil a political assassination in Berlin.)

Third in a four-volume publishing watershed during as many months, the book was followed by Nabokov’s Russian translation of Alice in Wonderland. The collection includes “Peter in Holland,” which also appears in 2012’s Vladimir Nabokov: Selected Poems, edited by Thomas Karshan.

Gornii put goes on the auction block in San Francisco on February 17. Better start saving those pennies.

[The above image of Gornii put is not of the volume for sale in February, but is the cover of an edition sold in December for $4,750 by the same auction house.]

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jan 18 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

During the course of writing The Secret History, I was staggered by the stories I heard from sources and translators whose family lives had been shaped in brutal ways by political prisons and concentration camps. Some, like Nabokov’s family, had fled Russia westward away from Revolution or pogroms, only to have to escape Germany or Poland or France as each fell under Hitler’s control. Others never set foot in Europe, yet the century’s police states and camps became part of their lives. This post is a small tribute to these families and their stories.

There were, of course, those whose relatives had been sent to German camps, which also claimed Nabokov’s brother, as well a key literary patron and others who had been part of his extended circle. Conditions at Neuengamme, for example—the camp outside Hamburg where Sergei Nabokov died—were horrific. Though it was not an extermination camp and conducted minimal medical experimentation, during its most brutal years starvation and forced labor killed most prisoners in weeks or months.

Then there were the lethal landscapes of the northern Gulag, which were detailed at length by a ninety-year-old former inmate of the mining camps of Vorkuta who welcomed me into his home. Sent to the Arctic after an altercation over military service, he worked for years in conditions so unforgiving that for millions, Vorkuta would come to represent the horrors of the system in a single word.

They were heartbreaking, inspirational, or depressing stories—sometimes all three at once. But they were not just about the Soviet Gulag and Nazi concentration camps.

They were heartbreaking, inspirational, or depressing stories—sometimes all three at once. But they were not just about the Soviet Gulag and Nazi concentration camps.

The wife of the Vorkuta survivor I met shared her story, too. She talked about being deported from Czechoslovakia to Germany during the war to work in a factory there. After Germany’s defeat, she was sent with thousands of other people to a British concentration camp, where she waited with her newborn son to return home. (Many former German camps were turned into holding facilities for populations awaiting repatriation, or prisons for suspected war criminals. In the case of Russian-held territory, some became Gulag outposts or transit camps for those who would be sent eastward as prisoners to the Soviet Union.)

Food that had been commandeered from French farmers during the war was no longer being freighted to Germany. Hunger was everywhere, even among those in the care of Allied troops. The woman’s baby died of health complications from the starvation conditions plaguing the camp. She eventually made her way back to Czechoslovakia alone. Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jan 17 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

Vladimir Nabokov was born in 1899, less than three years after the first concentration camps were founded thousands of miles away in Cuba. What does Vladimir Nabokov—creator of decadent fiction and king of literary insults—have to do with concentration camps? It’s a reasonable question.

Like Nabokov, concentration camps were born in the nineteenth century but came into their own in the twentieth. Slave labor and forced labor camps go back thousands of years, but the concentration camp—the pre-emptive, often extra-judicial imprisonment of a civilian population—is a relatively modern phenomenon. Nabokov himself explicitly traced the Soviet Gulag back to the earliest post-Revolutionary camps, “the torture house, the blood-bespattered wall,” and the “bestial terror that had been sanctioned by Lenin.” (See http://bit.ly/13I5lOr and http://bit.ly/V9YuvU.)

The Secret History argues that as Nabokov and the camps grew into their shared century together, he remembered them and recorded their existence in ways readers have missed—ways that transform his most famous works.

The Secret History argues that as Nabokov and the camps grew into their shared century together, he remembered them and recorded their existence in ways readers have missed—ways that transform his most famous works.

The term “concentration camp,” or “re-concentration camp,” was originally used as a phrase for any place people were gathered and housed for a particular purpose.

Today the German death camps of World War II provide the nightmare prototype for what we think of when we hear the words “concentration camp.” But the first appearance of the phrase in The New York Times actually referred to a new U.S. Army training center housing soldiers in 1898. (The same article shares the location of the camp, which, strangely enough, was listed as Falls Church, Virginia—where I live.)

Concentration camps as wartime detention facilities for civilians had actually debuted in Cuba two years before that first article. The Cuban camps had also been described in the Times, though some journalists were not yet calling them concentration camps.

Five years later, a story ran during the Second Boer War, quoting Times of London accounts of captives in the British concentration camps of Southern Africa. Afrikaner inmates were said to have detailed how healthy conditions were there, observing that “Boer women can play tennis all day if they like.” Just a month afterward, the Times was running reports that more than 12,000 civilians had died from conditions in the camps.

By mid-1903, the paper was publishing reports of atrocities and starvation in American concentration camps set up to relocate suspect populations and put down an insurrection in the Philippines. The Times likewise covered the German war against the Herero and Nama peoples in South-West Africa a year later, but did not describe role that transit camps and concentration camps came to play in the natives’ pacification and extermination.

The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov addresses these earliest concentration camps only in passing, but pays more attention to the next stage of development, which Nabokov was old enough to witness—the worldwide internment of civilians during World War I. Hundreds of thousands of noncombatants from every country in that conflict found themselves detained for years in barracks, behind barbed wire, in abandoned factories, in makeshift villages, or other improvised quarters.

Long before his younger brother Sergei died in a German concentration camp in 1945, Nabokov made key use of the camps of the First World War in an early novel—though it was largely overlooked. And in his Russian masterwork, The Gift, he used a story within a story to offer a nonfiction account of Russian prisons and hard labor outposts that were the forerunners of the Gulag, showing how nineteenth-century oppression under the Tsars helped create the revolutionaries who would turn labor camps to more widespread and crueler use during Nabokov’s lifetime. Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jan 11 2013

Filed In: News

Several news outlets are reporting that a group calling itself the “St. Petersburg Cossacks” may be responsible for vandalism that broke a window of the Nabokov Museum in St. Petersburg. A note inside a bottle found in the museum warned the staff of “God’s wrath.”

Some conservative Russians see Lolita as propaganda for pedophilia and object to Nabokov on moral grounds. This is the latest in a series of actions protesting cultural exhibits and places around the city seen as blasphemous or un-Christian, and may represent a first step toward using violence in these protests. Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jan 08 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

Love him or hate him for it, but Nabokov excels at depicting the exquisite intimacy of violence and the deliberate way one person exerts power over another. (For those who have read Nabokov’s most famous book, just recall Humbert Humbert erasing Lolita’s humanity as he recounts his appalling behavior in the novel’s sofa scene.)

A December 23 Washington Post review of a new novel about Soviet Russia reminded me of how the background threat of violence can carry a reader or viewer deep into a tale. Think of the most refined version of Hitchcock’s bomb-under-the-table scenario and how it’s amplified when one character contemplates in the moment whether or not to harm another.

In Stalin’s Barber, author Paul Levitt tells the story of Razeer Shtube, a Jewish man fleeing fascism and anti-Semitism in Albania for the bright promise of Soviet life under Stalin in 1930s Russia. The main character eventually ends up as barber to Stalin himself. Having been disabused of his notion of the magnificence of life in the Soviet Union, he comes to imagine how he might kill the monster who sits vulnerable before him. But like Nabokov, Levitt is smart enough to inject a kind of horrible comedy into the situation: the barber knows that the paranoid Stalin has body doubles, so the protagonist remains uncertain whether an assassination attempt would even eliminate the right man.

In Stalin’s Barber, author Paul Levitt tells the story of Razeer Shtube, a Jewish man fleeing fascism and anti-Semitism in Albania for the bright promise of Soviet life under Stalin in 1930s Russia. The main character eventually ends up as barber to Stalin himself. Having been disabused of his notion of the magnificence of life in the Soviet Union, he comes to imagine how he might kill the monster who sits vulnerable before him. But like Nabokov, Levitt is smart enough to inject a kind of horrible comedy into the situation: the barber knows that the paranoid Stalin has body doubles, so the protagonist remains uncertain whether an assassination attempt would even eliminate the right man.

Looking at Levitt’s CV online, I noticed that he had done a talk titled “Stalin’s Barber” at a European history conference in 2009. Asked last week by email about historical source material for his book, he mentioned that the talk he gave is also posted as a PDF. It reveals the lengths to which he went to give his story historical context—including nosing around for information about Stalin’s real barber, Karl Pauker, a former Hungarian hairdresser for the Budapest Opera.

Levitt spun his idea out from there, inventing his imaginary barber’s life. “I heretically think that some fiction and poetry can teach us more about the Soviets than the major biographies and histories,” he said in his 2009 talk, suggesting that at times fictional works can “communicate the truth in ways that primary sources cannot.”

This idea of a monstrous villain vulnerable to his barber recalls Nabokov’s short story “Razor,” in which the narrator, an émigré veteran of the Russian Civil War, endured a horrifying interrogation years ago in the Ukrainian city of Kharkov. (Nabokov would likely have known that Kharkov had been a particularly bloody prize in that war, having been traded back and forth between White and Red Army forces.) Now a barber in Berlin, the narrator one day recognizes his torturer sitting before him, a client in his barber’s chair. He contemplates killing the man. As he begins to shave his former interrogator, the barber reveals who he is, and then… Read more ›

Gornii put appeared less than a year after the death of Nabokov’s father, who helped prepare it for publication. (V.D. Nabokov was shot in March 1922 attempting to foil a political assassination in Berlin.)

Gornii put appeared less than a year after the death of Nabokov’s father, who helped prepare it for publication. (V.D. Nabokov was shot in March 1922 attempting to foil a political assassination in Berlin.) They were heartbreaking, inspirational, or depressing stories—sometimes all three at once. But they were not just about the Soviet Gulag and Nazi concentration camps.

They were heartbreaking, inspirational, or depressing stories—sometimes all three at once. But they were not just about the Soviet Gulag and Nazi concentration camps.