Nabokov, metadata and civil liberties

“I wanted to be a famous spy.”—Humbert Humbert

Vladimir Nabokov disdained most novels as “topical trash” and sought to create something transcendent in his own fiction. Yet topics dominating this month’s news about Edward Snowden—government surveillance, political intrigue, and spying—are oddly timeless when it comes to looking at Nabokov’s world.

Vladimir Nabokov disdained most novels as “topical trash” and sought to create something transcendent in his own fiction. Yet topics dominating this month’s news about Edward Snowden—government surveillance, political intrigue, and spying—are oddly timeless when it comes to looking at Nabokov’s world.

Growing up in the twilight of Russian Empire, where his father was first imprisoned under the Tsar in 1908 and then arrested under Lenin in 1917, Nabokov was familiar with state-sponsored surveillance and informers from both ends of the political spectrum. In Speak, Memory, he notes the evening his father’s librarian discovered a Tsarist stooge in a back room eavesdropping on a meeting. After the Revolution a family retainer led Soviet sympathizers to the hidden safe containing the Nabokov family jewels. And at the dawn of Russia’s civil war, Nabokov was himself captured in the hills above Yalta and interrogated on suspicion of signaling the British with his butterfly net.

After his father’s death in 1922 at the hands of reactionaries trying to assassinate someone else, Nabokov finished his university studies and then returned to Berlin. Through the Weimar era into the Nazi rise to power, the city remained a playground for double agents, with a reputation as the Soviet central bureau for espionage abroad.

During these years, Nabokov was said to make ill-advised jokes over the phone with a Jewish friend about when their (non-existent) Communist cell should meet. His short story “The Assistant Producer” tells a thinly veiled tale of Russian singer Nadezhda Plevitskaya, who went to prison for espionage and collaborating with her husband’s murderous intrigues. Nabokov’s novel Glory includes the drama of illicit border-crossings into Soviet Russia by anti-Bolshevik revolutionaries.

Early on, he developed a distaste for petty bureaucracy and laws that allowed “rat-whiskered consuls and policemen” to harass innocent refugees. He believed such thuggery could lead to the automated machinery of a police state in which massacres become “only an administrative detail.”

He would go on to write two novels that deal directly with totalitarian dystopias. In Bend Sinister, a bumbling group of informers and agents of the state try to enforce conformity. In Invitation to a Beheading, the state monitors and prosecutes corrupt thinking. In both, the protagonist faces execution.

Nabokov in America

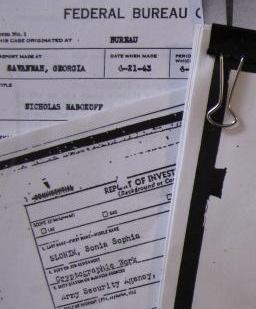

Even after Vladimir and Véra escaped to America in 1940, Nabokov’s brushes with intrigue and spying continued. Véra’s sister Sonia had been fraternizing with a known propagandist for the Nazis, and as she made her way from France to Casablanca to America, a telegram delivered to the U.S. Secretary of State warned Americans of French suspicions that she was a spy. Sonia was allowed to enter the country, but a “mail cover” was put on her correspondence—a pre-digital era metadata collection in which senders’ and recipients’ names were recorded without opening the mail itself.

After the war, Sonia moved to Arlington, Virginia, as a cryptographer for the U.S. Army Security Agency. Nabokov’s cousin Nicholas, who had done work for the US government during the war, was chosen over Vladimir to head up programming for the State Department’s Russian-language radio broadcasts. As both Nicholas and Sonia sought work in sensitive intelligence positions, loyalty investigations were launched against them. Sonia’s case focused on whether she had Communist or German sympathies and was a blackmailer. Nicholas’ investigation centered on government anxiety that Nicholas might be homosexual.

Both accusations seem unfounded in retrospect. But Sonia’s bank records were examined, various lies about her were put on the record by informants, and several people were interviewed about her life in Europe and America (including Vladimir and Vera Nabokov, whose portion of Sonia’s file is posted here). Nicholas faced a more invasive investigation, in which his medical records were pulled, and his doctor provided agents damaging details of his mental health history.

Meanwhile, McCarthyism was in full swing and targeting some of Nabokov’s associates. Close friend Edmund Wilson’s Memoirs of Hecate County was called pro-Communist pornography. Critic Marc Slonim (whom Nabokov incorrectly believed was taking money from the Soviets) was hounded for years and forced to testify before the Jenner Committee on Capitol Hill. His employer, Sarah Lawrence College, resisted pressure to dismiss him.

Nabokov once clarified his political stance as not in favor of any particular system, but focused on a handful of restrictions, among them: “Portraits of the head of government should not exceed a postage stamp in size. No torture and no executions.”

A die-hard anti-Communist, he shared some of the complicated feelings of the American public today when it came to rooting out perceived threats to American security. He believed in free speech, yet during his years teaching at Cornell also befriended his local FBI agent. (This under Hoover’s reign, and at a time when many college professors were markedly unenthusiastic about federal investigations into institutions of higher learning.)

Vladimir and Véra were both reluctant to condemn McCarthy, and Véra believed that the American educational system had been hopelessly infiltrated. Like her husband, she claimed to support civil rights. As student protests became widespread, however, she had no problem criticizing the leniency shown to activists, suggesting that “‘hooligans’ should be put away—for good.”

If Véra had her own strong opinions on student life, Nabokov maintained a streak of anxiety over civil liberties. He was no joiner, and not a social activist, but his son Dmitri once shared a revealing story about the sixty-four-year-old Nabokov. After the assassination of President Kennedy, Dmitri recalled his father watching news reports of the arrest of Lee Harvey Oswald (likely this midnight press conference where a battered Oswald claimed a policeman had hit him and asked for a lawyer). In the moment, Dmitri recalled his father’s concern that Oswald might be innocent and the police had “worked over this poor little guy needlessly.”

It was not that Nabokov did not care about assassinations—he was more than aware of the dangers of political instability. And it was not that he somehow did not long for justice—he himself had revenge fantasies about Stalin, Lenin, Hitler, and the German perpetrators of the Holocaust.

Nabokov’s literary magic didn’t flow from vague convictions but rose out of dazzling specifics. Perhaps in sympathy with his civil-rights crusader father, Nabokov’s personal code was likewise bound up with individual liberties rather than social movements. As with Humbert Humbert and Lolita, so with policemen roughing up Lee Harvey Oswald, or rat-whiskered consuls persecuting the innocent. Each encounter in the end comes down to what one human being is willing to do to another. And Nabokov understood how tempting it is for those who are given power to abuse it.