From the Pogues to Lolita, a tale of literary revenge

What does the Pogues’ Christmas song “Fairytale of New York” have to do with Lolita? The trail links at oblique angles but leads to a story of betrayal, obscenity, and revenge that would have pleased Nabokov, if only he had lived to hear it.

The Irish band’s 1987 carol for the Grinchiest among us tells of a pair of fresh-faced lovers ground down by the Big Apple and reduced to Edward Albee-style fury. The vituperation begins with “you’re a bum, you’re a punk / you’re an old slut on junk” and goes downhill from there.

Jem Finer of the Pogues took the title from the book he was reading when he co-wrote the song: the novel A Fairytale of New York by J.P. Donleavy. Donleavy—like Nabokov—was long notorious for his taboo content and sexual themes. In Donleavy’s Fairytale, a man returning to New York with his wife’s corpse meets up with a woman whose millionaire husband has also just died. Donleavy told the BBC that he likes the song but on hearing it “realised straight away that it didn’t really have anything to do with my book.”

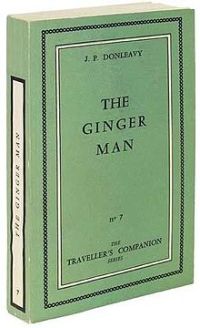

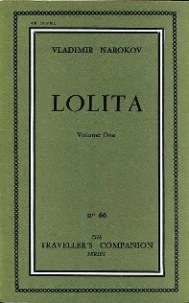

How does “Fairytale” connect with Nabokov? Donleavy leapt to prominence with The Ginger Man in 1955, the year Lolita was published. Nabokov invented a story of a European immigrant’s sexual depravity in America; Donleavy wrote of an American’s sexual adventures in Europe. Both authors steamrolled postwar obscenity standards and found their books’ distribution hamstrung by censorship. Both nevertheless went on to sell tens of millions of copies (The Ginger Man only slightly less than Lolita).

How does “Fairytale” connect with Nabokov? Donleavy leapt to prominence with The Ginger Man in 1955, the year Lolita was published. Nabokov invented a story of a European immigrant’s sexual depravity in America; Donleavy wrote of an American’s sexual adventures in Europe. Both authors steamrolled postwar obscenity standards and found their books’ distribution hamstrung by censorship. Both nevertheless went on to sell tens of millions of copies (The Ginger Man only slightly less than Lolita).

Most importantly, both novels made their debut with Olympia Press, the Parisian publishing house run by Maurice Girodias. With recent titles including works by Samuel Beckett and Jean Genet, Olympia was known for publishing sexually frank but serious literature, and seemed (however briefly) like it might offer an appropriate home for Lolita and The Ginger Man.

From before he signed with Olympia, Nabokov suspected that his story of a nymphet and her tormentor might only find a home in Europe at a sketchy publishing enterprise. So when that suspicion turned into reality, Nabokov appears to have been less shocked than Donleavy to find his book included in the Traveller’s Companion series that would eventually encompass Tender Was My Flesh, White Thighs, and Until She Screams. Donleavy told the Guardian in 2004 that

“When I discovered that the novel was published in this pornographic series, I realised I would never have any reputation, that the book would never exist in any real form – it was just a piece of pornography. It wouldn’t get any reviews. It was a total nightmare.”

He says he vowed revenge on Girodias once he discovered the fate of his book, swearing that “if it were the last thing I ever did, I would redeem and avenge this work”.

As Girodias alternated posing as a high-minded litterateur with frank identification as a pornographer, Nabokov likewise began to take against him. His distaste only intensified after Lolita began drawing international attention and Girodias demanded staggering percentages in exchange for overseas rights to the book, threatening to distribute it in America himself. Nabokov began to look for ways to exit his deal with Olympia, twice wishfully declaring his contract void. He would end up in litigation that continued more than a decade after Lolita’s publication, when a French court finally closed the book on legal obligations between Nabokov and Olympia.

Donleavy’s struggle with Girodias would continue for longer. As the Guardian describes it, after more than two decades of legal battles, in which the proceeds from The Ginger Man likely helped fund both parties to the suit, Girodias tried to buy back the name Olympia Press at a bankruptcy auction. Donleavy sent his then-wife Mary to France, where she made the final bid and ended up purchasing the Olympia name for Donleavy, taking it forever from the man he felt had misrepresented his book from the beginning.

Donleavy’s struggle with Girodias would continue for longer. As the Guardian describes it, after more than two decades of legal battles, in which the proceeds from The Ginger Man likely helped fund both parties to the suit, Girodias tried to buy back the name Olympia Press at a bankruptcy auction. Donleavy sent his then-wife Mary to France, where she made the final bid and ended up purchasing the Olympia name for Donleavy, taking it forever from the man he felt had misrepresented his book from the beginning.

In his Lectures on Literature, Nabokov wrote that “great novels are great fairy tales.” Nabokov had also thought a good deal about fairy tales themselves, building subtexts incorporating their darker incarnations into his novels, from “Cinderella” in Pnin to “Der Erlkönig” in Pale Fire. And while music seems primarily to have been an irritant to him, Nabokov might well have appreciated the spirit of “Fairytale,” a song that withholds easy sentiment while acknowledging how close love and resentment sit to each other.

In the end, Donleavy and Nabokov each probably owe Maurice Girodias a debt of gratitude for taking a chance on their breakthrough novels—but Girodias also inspired a more-than-justified revenge from both men. It’s a kind of Nabokovian happily ever after, one rooted in payback and destitution. Not unlike the Pogues song, which—as with Nabokov’s best works—also has a hint “of malice at the back of [its] voice,” a streak of uncertainty, and joy.

Happy holidays.