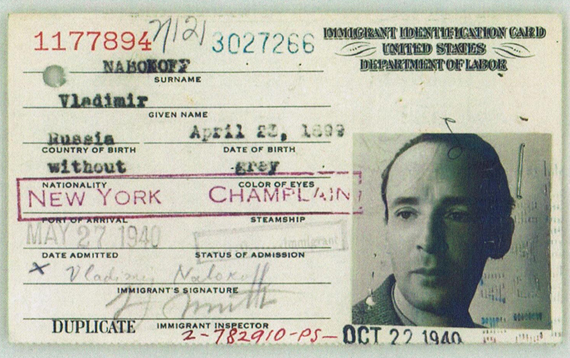

Vladimir Nabokov’s immigration file

It’s pretty neat what you can learn from government archives. The first image series to be posted on the Records page of this site is Vladimir Nabokov’s immigration file, with documents spanning 1940 to 1945. Aside from pictures of the author, which are always interesting, the government forms offer their own sly narrative of Nabokov’s first years in America.

Born in Russia, Nabokov arrived officially as a man with no country (“without nationality” on the forms). He had fled his homeland before the formation of the Soviet Union in 1922 and so never became a Soviet citizen. Those who have read his short stories or autobiography know of the nightmare bureaucracy facing travelers, like his wife Véra and himself, who held only Nansen refugee passports.

The forms also show that though it had not yet entered the war when Nabokov arrived on its shores, America was very keen on keeping revolutionaries out. Travelers had to vow shipboard that they were not anarchists, and again on arrival, and again when they filled out their declarations of intent to become American citizens.

Pale and still recovering from influenza when his French doctor prepared his paperwork, Nabokov had more than the flu to keep him lean. After fleeing Hitler’s Germany for France, he and his wife Véra had struggled to keep their pre-school-age son Dmitri comfortable, but it’s pretty clear they themselves had been living at a bare subsistence level, due at least in part to legal restrictions barring them from work. Months after his arrival in America, Nabokov’s height was listed at 5’11”* and his weight at a still-skeletal 124 pounds. By the time he became a U.S. citizen in 1945—a few months after he had quit smoking and taken up molasses candy—he had gained more than 50 pounds.

His vocabulary for himself, too, transformed between his arrival in America and official U.S. citizenship. His eyes, which were “gray” (and “grey”) on his paperwork in 1940, become “hazel” by 1945. Not only is hazel a more Nabokovian word (think of the tragic Hazel Shade in Pale Fire, and L. Haze, otherwise known as Lolita), the change allowed him years later in his autobiography to make a quip about Hazel Brown.

In the interest of keeping things interesting (and sometimes in the interest of privacy), I won’t be reproducing every file in its entirety on the Records page. But the fourteen images in this series do represent Nabokov’s complete immigration file.

[Click on any image in the file to get started, and use left and right arrow keys in the side margins of each image to scroll between pages.]

*Nabokov originally listed himself at 5’8″ in his visa application, prepared in France, but three other, later listings of his height in his immigration file declare he is 5’11”. When I interviewed Michael Scammell about meeting Nabokov in person before translating two of his novels from Russian to English, one of the things Scammell remarked on was Nabokov’s relative height. So I have taken the 5’11” as the correct number of the two.

There are 4 Comments to "Vladimir Nabokov’s immigration file"

Nabokov scholar and poet Matthew Roth has noted on Facebook that Hazel may not be at all a more Nabokovian color than grey/gray. And right he is! We should surely not forget Pale Fire’s many shades of grey, including Jack Grey himself.

The “anarchist” question was a routine one at Ellis Island, dating back to at least 1920, when my grandfather was asked it. He answered correctly.

I would think the VNs’ biggest obstacle to entry was that Vera was Jewish. Quotas on Jews were very restrictive. According to Doris Kearns, in 1939 Roper “found that 53% of the Americans asked believed Jews were different from everybody else and that these differences should lead to restrictions in business and social life.”

Yes, Joe–the anarchist question existed even before 1920, in tandem with fears of threats to government worldwide spawned by the Russian Revolution. Jews were not just seen as different, but also widely held to be responsible for the Revolution. As a result, fears of anarchists and Jews were often conflated by both the U.S. government and the general population.

The challenge that immigration quotas presented to Jewish refugees during WWII plays a key role in “The Secret History.” I’ll be leaving a lot of that for readers of the book, but I will post about some of the details from Vera’s immigration file early next week…

[…] Curious about Vladimir Nabokov’s immigration file? Check it out. […]