Happy birthday, Nabokov! What does the FBI have on you?

When is Vladimir Nabokov’s birthday anyway? Depending on where you look, you’ll see April 10, April 22, and April 23 listed, but which is it?

The answer is… all three. As Nabokov explains in his autobiography, Speak, Memory, he was born in Russia in 1899 on April 10, but at that point in time Russia was still using the Julian calendar, rather than the Gregorian calendar in place in the West. April 10, 1899 under the Julian calendar in Russia was the same day as April 22, 1899 in much of Western Europe and America. April 10, 1899 would be Nabokov’s “Old Style” birthday, and April 22, his birth date in the “New Style.”

After the Revolution, Russia joined the West in adopting the Gregorian calendar, which left émigrés using both systems for a few years. Rul, the newspaper Nabokov’s father edited in Berlin, for example, continued to use Old and New Style dates for several years.

So where does April 23 come from? Well, celebrating a day later allowed Nabokov to distance himself from Vladimir Lenin (born Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov), who also arrived in the world on April 10/April 22, nearly three decades before Nabokov’s birth. But another quirk of the conversion from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar was that the Julian calendar had certain leap days that the Gregorian calendar dropped.

So while the difference between the two calendars was twelve days in 1899, in 1900, the gap expanded one additional day, to 13 days. April 10, 1899 converts to April 22, 1899, but by the following year April 10 became April 23. Nabokov was born on April 22, but celebrated his first birthday on April 23, which was, according to the Gregorian calendar, the day he turned one.

Enough about birthdays. What about declassified FBI files?

Nabokov and the FBI

Readers of The Secret History will know how caught up the Nabokovs’ family members were in intrigue, espionage, and intelligence matters, from the murky days of vague diplomatic missions, polyglot tendencies, and code-breaking skills of Nabokov’s uncle Ruka in pre-Revolutionary Russia to other relations’ clearer links with US Army Intelligence and CIA anti-Communist efforts decades later.

After the war, Nabokov had tried to get a State Department job that ended up going to his cousin Nicholas. For most of the first decade of the Cold War, he taught at Cornell University, where his direct involvement with US-Soviet political turmoil consisted of befriending the FBI agent tasked with keeping an eye on the campus. (During these years, then-Vice-President Richard Nixon requested an investigation into communism at American colleges and universities, and the FBI created a series of reports on individual schools, charting the degree to which they believed communist elements had infiltrated each institution.)

But as a Russian émigré in an era in which Russians had become suspect, did Nabokov merit investigation by the FBI? Did the FBI have anything on Nabokov?

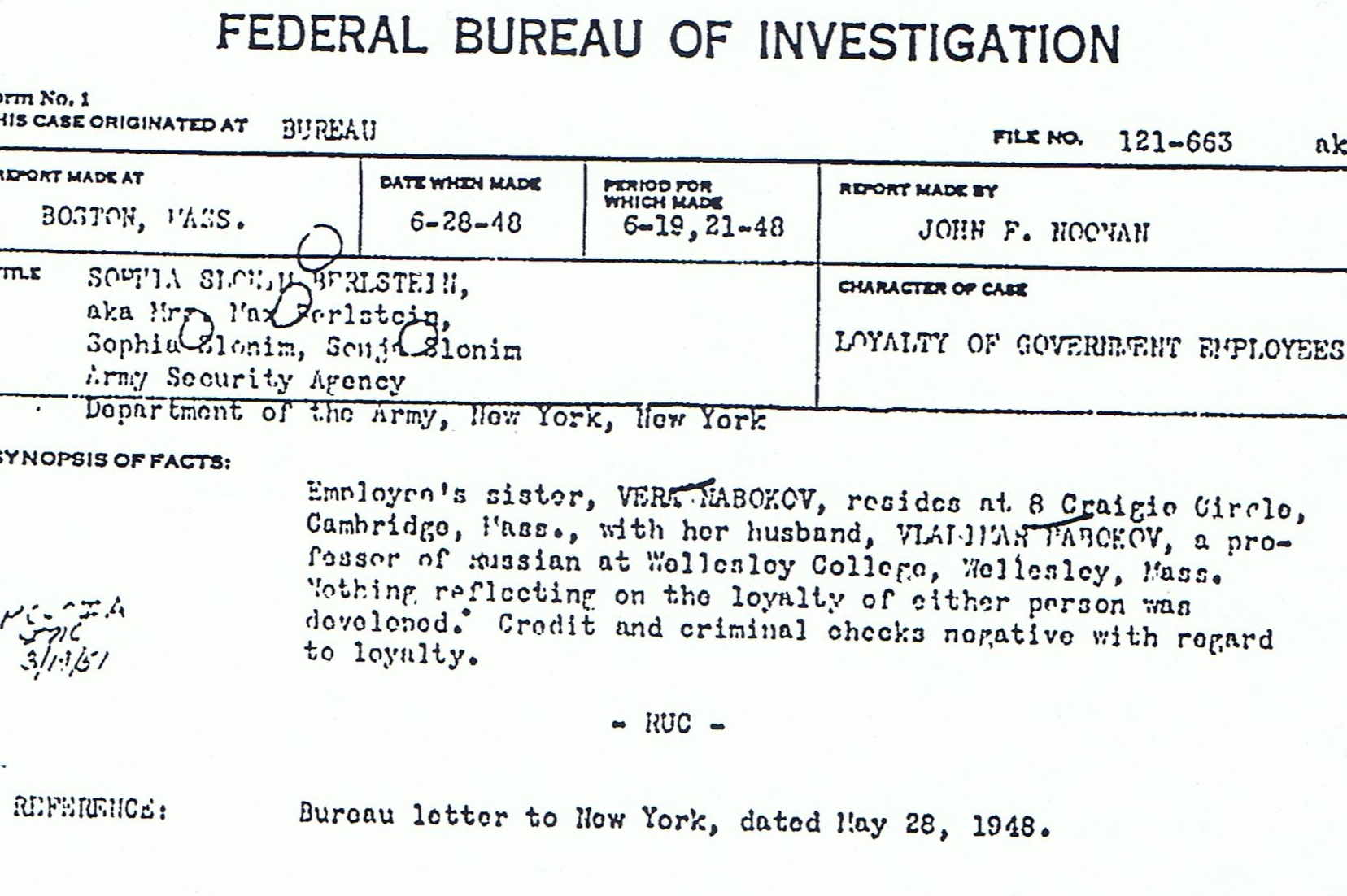

The only FBI files on Vladimir Nabokov divulged to date are very thin and come not from any investigation centered on him, but one focused on Sonia Slonim, the younger sister of his wife Véra.

Sonia had dabbled in intrigue during the war, and her FBI file is extensive. I’ll write more on her later, but for now, suffice it to say that an international loyalty investigation on Sonia in 1948 caused agents to visit Vladimir and Véra Nabokov, then still in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The investigators ended up submitting three less-than-full pages on the couple, which were summarized in a fourth. Here’s a detail from the summary page looking into “VLADIMAR” and VERA NABOKOV (click each image to see the full page):

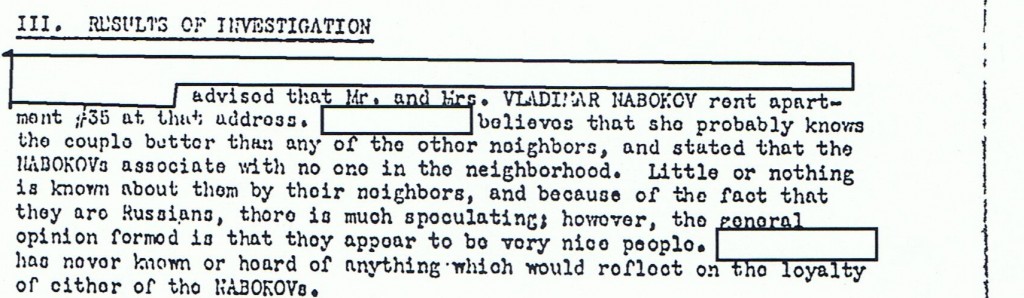

The second page reports that the Nabokovs’ Russian background inspired speculation, which the informant—a neighbor—believed was unfounded.

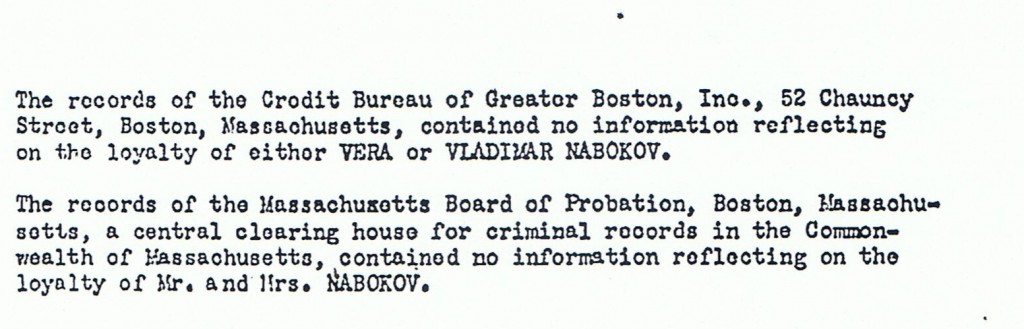

The third page details their criminal records (which did not exist) and their financial situation, finding no red flags related to loyalty to their adopted country (usually large sums of money coming in or suspicious payments made to others).

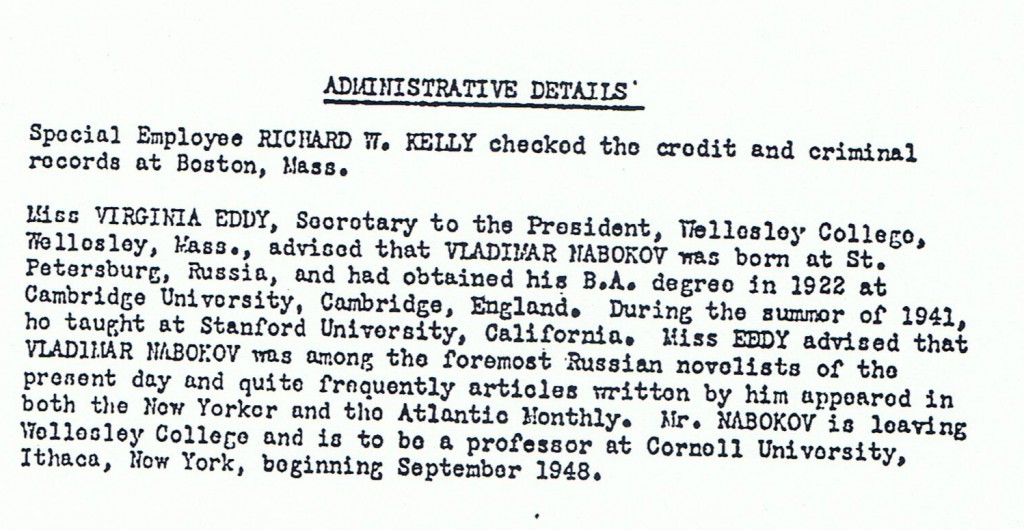

The last page lists the investigators and non-confidential informants interviewed for the report. Though Nabokov was seen by some on campus as a reactionary at the time, Virginia Eddy clearly thought highly of both Nabokov and his reputation.

Vladimir and Véra got a quick, clean bill of health from FBI agents. But things were not so simple that year for Sonia Slonim or Nicholas Nabokov, both of whom faced complex and wide-ranging investigations, for very different reasons.

I’ll post additional excerpts from both their FBI files in the coming weeks. And in the meantime, happy 114th birthday to Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov!