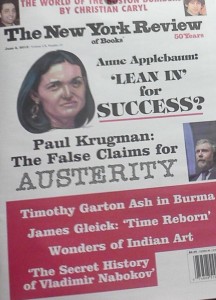

The New York Review of Books looks at The Secret History

Nabokov had a complicated relationship with his critics, not least Edmund Wilson, whose 1965 review of Eugene Onegin in The New York Review of Books put a stake through the heart of their friendship. Here’s Wilson’s opening line:

This production, though in certain ways valuable, is something of a disappointment; and the reviewer, though a personal friend of Mr. Nabokov—for whom he feels a warm affection sometimes chilled by exasperation—and an admirer of much of his work, does not propose to mask his disappointment.

Yesterday, I had my own experience being reviewed in the NYRB. University College London professor Mark Ford had the honor of doing the carving up, in a group review. It’s out from behind the paywall now, so you can read it yourself, but I’ll do a quick survey and include a quote or two from it here.

Ford didn’t open with Wilson’s directness, starting instead with a summary of Nabokov’s life before diving into my book. He noted a few of the echoes between Nabokov’s younger brother, Sergei, and Pale Fire narrator Charles Kinbote high in the piece, which I was glad to see, because The Secret History is the first real exploration of that link, and it’s an important part of the book.

Ford didn’t open with Wilson’s directness, starting instead with a summary of Nabokov’s life before diving into my book. He noted a few of the echoes between Nabokov’s younger brother, Sergei, and Pale Fire narrator Charles Kinbote high in the piece, which I was glad to see, because The Secret History is the first real exploration of that link, and it’s an important part of the book.

Ford had some nice things to say, though he wasn’t a fan of my style. He liked the use of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Soviet dissident and Gulag survivor, in counterpoint to Nabokov as the framework of the narrative. He also praised my “exemplary primary research,” which, he suggests, “forces one to consider several fascinating quandaries presented by Lolita and Pale Fire.”

At some point, if I get just a little bigger pool to draw from, I’ll do a quantitative analysis of reviews of The Secret History, to see what that might offer in some larger sense about book reviews and reviewers. For now, I’m resisting posting more of the review here for fear of disappearing down a rabbit hole of quote and response that would surely be more boring than the unbelievably dull but angry quibbles that Wilson and Nabokov had over the finest points of Eugene Onegin.

Compared to the insults lobbed between Wilson and Nabokov, Mark Ford’s praise is generous and his criticism mild enough. It’s an honor to have the book featured in a place that will allow some of the questions I’ve raised—about Sergei Nabokov and Charles Kinbote, about anti-Semitism and Humbert Humbert—to be on the record as part of a conversation about Nabokov’s writing and the history that helped make it.

If you’re so inclined, you can spend your lunch hour reading the NYRB review for yourself. And here are the other books featured later in the piece—The Tragedy of Mister Morn, Selected Poems, Stalking Nabokov—all of which are worth some time, particularly Mister Morn, if you’re interested in Nabokov’s early writing or Revolutionary Russia.