Hiding history in fiction: Nabokov’s Proustian wink

Tomorrow The Secret History will be published! I’m headed up to New York to do my first interview for the book. But before it drops, I wanted post a quick note on something important.

I’ve spent the last five years exploring the links between Nabokov’s fiction and the world in which he lived. There’s a danger to this approach—you can get caught up in things like, “This tree can be seen from the rear windows of the Museum of Contemporary Zoology at Harvard (where Nabokov helped curate butterfly collections in the 1940s). He must have looked out on it during the years he was writing Bend Sinister.” And no doubt about it—there’s a certain charm to tracing Nabokov’s life or seeing things that might have inspired him.

But a relentless search for links like these sometimes doesn’t lead to any greater understanding of what a writer has accomplished—after all, the magic is in the transformation. I, too, might look down on that same tree, but I can’t write Bend Sinister, let alone Lolita.

But a relentless search for links like these sometimes doesn’t lead to any greater understanding of what a writer has accomplished—after all, the magic is in the transformation. I, too, might look down on that same tree, but I can’t write Bend Sinister, let alone Lolita.

Nabokov himself resisted these connections, telling his Cornell students that Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time was not autobiography but fantasy, “just as Cornell University will be a fantasy if I ever happen to write about it some day in retrospect.”

The enchantment the author casts is the most sublime aspect of a great book, Nabokov argued, and to look to fiction to say something about history or the time and place in which it is set is foolish.

Except when it isn’t. I suspect that when he made those statements, Nabokov himself only half-believed them. Even then, he pointed out to his students reading Mansfield Park that one character’s trip to Antigua recalls the plantations there and the cheap slave labor that had built the family’s fortune.

What’s more, by the time he arrived at Cornell, he had been working toward something different for nearly two decades. The fiction he wrote after his teaching years would most directly counter his own arguments. By the time he got to 1962’s Pale Fire, he let one character directly make a plea for a revised view.

In the novel, the distraught, unbalanced Charles Kinbote is not invited to his friend Shade’s birthday party. After the party is over, as a gesture of reproach, Kinbote waylays Shade’s wife and hands her a volume of In Search of Lost Time to pass along to her husband. He recites a monologue of his own invention:

…you remember we decided once, you, your husband and I, that Proust’s rough masterpiece was a huge ghoulish fairy tale, an asparagus dream, totally unconnected with any possible people in any historical France, a sexual travestissement and a colossal farce, the vocabulary of genius and its poetry, but no more…

In his monologue, Kinbote goes on for some time with descriptions of the book, and then comes to the heart of his speech:

…but–and now let me finish sweetly–we were wrong…

Kinbote is using a scene in Proust’s novel about not being invited to a party to point to something in his own life—the party he was not invited to. But in Kinbote’s words to Shade’s wife, Nabokov is also speaking over the heads of his characters to his readers. In Search of Lost Time was the very book Nabokov had, more than a decade earlier, told his students should not be read as autobiography, and that there was no purpose to seeing it as anything but fantasy.

There is no doubt that to reduce a book to its biographical factoids is to kill it. But to completely avoid the existence and influence of the writer’s raw material can be equally muddleheaded. I’m suggesting that the solution Nabokov came up with was to take advantage of readers’ tendencies to look for clues by using these connections in a surprising new way to say something about the time and place in which each novel is set.

Kinbote’s description of Proust could just as easily sum up so many dismissals of Lolita: “a sexual travestissement and a colossal farce, the vocabulary of genius and its poetry but no more.” But by leaving clues of geography and chronology in his books, could Nabokov have been pointing to tragedies that had overtaken his world during his own century? Could Nabokov, who loathed art that explicitly subjugated itself to politics, have written novels of social commentary in which moral and political indictments were buried but left for the reader to find?

The demented Charles Kinbote forces his fantastic, unbelievable stories of the lost past relentlessly into every nook and cranny of Pale Fire. But The Secret History argues that Kinbote, like his author, is transforming horrific real-world raw material into a fairy tale, hiding history Nabokov knew and cared deeply about. Lolita, too, becomes even more the story of the postwar American landscape in which it is set.

Sometimes looking for links between historical events and literary achievements can flatten a story; at other times (as Martin Gardner showed with The Annotated Alice) it can reveal equally extraordinary things tucked beneath the surface tale. In the case of Nabokov, his fiction carries forgotten history inside it like a time bomb waiting to detonate.

———

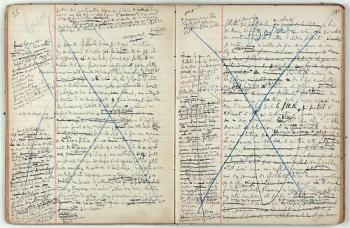

Image: Two pages from Marcel Proust’s manuscript for In Search of Lost Time