Pnin, the Cremona Women’s Club, and Jewish refugees after the war

Nabokov was crazy for complex allusions, intentionally seeding his fiction with literary and historical references, from pop culture and epic poetry to both in a single line (see “Chapman’s Homer” from Pale Fire). But there are so many winks and nods and proper names in his books, sorting out what has coherence from what is coincidence can be a vexing challenge.

In many ways, of course, it doesn’t matter. Readers reinvent a story based on their own knowledge and experience, and whether Nabokov intended them to make certain connections or not doesn’t render any particular association illegitimate.

But when writing The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, I was exploring in part the degree to which Nabokov had planted concentration camp history and references in his work. For my purposes, the question of what Nabokov meant became relevant.

But when writing The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, I was exploring in part the degree to which Nabokov had planted concentration camp history and references in his work. For my purposes, the question of what Nabokov meant became relevant.

In some cases, there is no question of what he was doing. When the Nabokovs wrote a note to a translator of Bend Sinister to point out that the phrase “ghoul-haunted Province of Perm” was meant in part to evoke the notorious Soviet labor camps of Perm, we can be fairly certain what Nabokov was up to.*

And though it has been largely ignored, when Hermann, the narrator of Despair, mentions being interned near Astrakhan in southern Russia from 1914 to 1919, there is little doubt that Nabokov sentenced his character to the kind of early pre-Gulag, pre-Holocaust concentration camps that did in fact exist in and around Astrakhan during those years.

But other references are more enigmatic or convoluted. Nabokov’s novel Pnin provides a lovely example of something that fascinated me and was promising but that I ultimately didn’t use.

Professor Timofey Pnin is a poster boy for bumbling and hapless foreigners trying to make a place for themselves in postwar America. His adventures provide near-constant comedy for the reader, from his infatuation with his landlady’s washing machine to his chronic mangling of the English language. But in addition to witnessing Pnin’s comic antics, the reader learns that his life has been touched again and again by tragedy. One key sorrow involves his childhood sweetheart, the Jewish Mira Belochkin, whose death at Buchenwald obsesses him even as he tries to forget it in an attempt to remain sane. The presence of Buchenwald in the book makes clear that Nabokov was thinking of concentration camp history in the pages of Pnin.

The novel’s structure is a wonder, and opens and closes with a story of Pnin giving a talk to a Women’s Club in the American town of Cremona. The reader follows Pnin’s mishaps in agonizing detail. But is there any significance to the name Cremona?

The other Cremona

Cremona is most famously a city in northern Italy a little over 50 miles southeast of Milan. Home to some of the most extraordinary violin makers in history—including Antonio Stradivari—Cremona is a cultured, genteel city with a long history of anti-Semitism going back four centuries to the papacy of Julius III.

Cremona is most famously a city in northern Italy a little over 50 miles southeast of Milan. Home to some of the most extraordinary violin makers in history—including Antonio Stradivari—Cremona is a cultured, genteel city with a long history of anti-Semitism going back four centuries to the papacy of Julius III.

During World War II, Cremona was known for its incendiary anti-Semitic publication, the Regime Fascista of Cremona. News reports in Europe and America reported its extreme calls for the expulsion of Jews from public life across Italy.

This two-sided identity—the height of art and the depths of bigotry in one geographic setting—echoes the strange regret voiced by Dr. Hagen in Pnin, who mourns not Buchenwald’s existence but the fact that it had been built so close to the cultural heart of Germany.

Cremona was also a concentration camp, but not in the way that we usually think of camps today.** From 1945 to 1947, it was an Allied concentration camp after the war—a temporary internment camp primarily for European Jews. Housing more than a thousand refugees as they awaited emigration (some fleeing Soviet-held territory, some released from far more lethal Eastern European concentration camps), Cremona was among the better-organized camps for displaced persons. But even so, severe food and clothing shortages resulted in more than a hundred deaths in just one six-month period.

Linking the fictional town of Cremona to its historical namesake does relate to some of the themes and concerns Nabokov outlined in Pnin. I found the story of postwar Jewish refugees waiting to leave Cremona centuries after all Jews had been expelled from the town very moving, and I was tempted to fold this history into my book.

But despite Pnin’s obsession with the Jewish Mira Belochkin, despite his sensitivity to the larger history of human suffering and the Holocaust, despite his standing before the people of the invented American town of Cremona bearing interior witness to those he has himself lost amid the murderous chaos of the century, in the end there were simply not enough connections linking Pnin, Nabokov, and Cremona, Italy, for me to include its story in The Secret History.

Cremona’s anti-Semitic public face and its identity as a concentration camp had been covered in national newspapers, including a hunger strike that internees began in 1945 to protest British policies delaying their emigration to Palestine. And Nabokov clearly nodded at least once in Pnin to the Italian Cremona, referring to the American town’s “mellow Italian name.” But I never felt conclusively that he was aware of Cremona’s bleaker history. Stories about Cremona in the 1940s did not seem to have been omnipresent enough in publications Nabokov read, and the Italian Cremona was not woven into Pnin in a way that pointed directly to its postwar identity as a camp. So I let it go.

These kinds of associations came up again and again during my research. Exploring concentration camp history in the context of Nabokov’s writing was an education in the omnipresence of the camps that came into the twentieth century with him, and the degree to which history lives on in language and can wind its way into our stories, whether an author intends it or not.

[For pictures from the Cremona camp for displaced persons, see this U.S. Holocaust Memorial collection of photos.]

———

*See Brian Boyd’s Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years, p. 316.

**For the history of the phrase “concentration camps” and the evolution of the camps across Nabokov’s lifetime, read this January post.

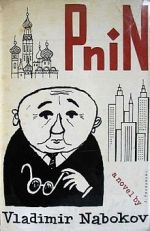

Images: Top, the cover of Nabokov’s novel Pnin; bottom, Antonio Stradivari, arguably the most famous native of Cremona, Italy.