Remembering Ardis: a note from Fred Moody

[The first in a series of guest posts on Nabokov and history.]

When I first heard about the forthcoming publication of The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, I pre-ordered the Kindle version immediately. I was hugely curious about the book, as I humbly thought I knew pretty much everything there was to know about Nabokov’s history. I had worked during the 1970s at Ardis Publishers, a publisher of Russian literature that dealt regularly with the Nabokovs during my time there, and had seen a secret side to Vladimir and Véra that was viewable only to those of us at Ardis.

I started reading with a smug air, and ended up surprised by the book’s revelations. The careful tracing in The Secret History of concentration-camp and anti-Semitism themes running (often cryptically) throughout Nabokov’s life and novels furnishes proof of the author’s deep political engagement—a stance concealed brilliantly by the public pose he struck during his life as an artist who resolutely disdained the political. More to my point here, the revelations brought back vivid memories of the quiet, kind-hearted political engagement we at Ardis regularly witnessed in the Nabokovs.

So The Secret History managed the paradoxical trick of both surprising me and confirming what I already knew.

Ardis Publishers (the name comes from the name of the country estate in Nabokov’s Ada) was founded by Carl and Ellendea Proffer in 1971. At that time, Carl was a leading Nabokov scholar and perhaps the west’s foremost authority on contemporary Soviet literature. The Nabokovs greatly admired his Keys to Lolita, which remains, in my view, the best exploration of the ingenious (and ingeniously misleading) system of literary allusions and their meaning in that brilliant novel.

The mission at Ardis was threefold: to publish, in Russian and English, the work of suppressed contemporary Russian writers and poets who could not publish in the Soviet Union; to reissue classic works of 20th-century fiction and poetry that had been censored out of existence in the Soviet Union, and to smuggle these editions back into the USSR; and to promote, in the western world, purely literary suppressed Soviet writers, as opposed to those, like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who were famous in the west for largely political reasons. There was a rather large number of gifted Soviet literary figures who couldn’t garner much interest in the west unless they were also political figures.

So we had an intense sense of mission at Ardis—one considerably heightened by the cloak-and-dagger nature of a lot of our work. Our reissued Russian-language books by some of the greatest Russian writers of the century (Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, Marina Tsvetaeva, Nikolai Gumilev) were printed in little pocket-sized editions that were easily smuggled. “Companies” with such murky names as “International Literary Associates” would buy hundreds, sometimes thousands of copies at a time; we always suspected, but never knew for sure, that they were CIA fronts.

There was a great deal of back-and-forth between Ardis and Soviet writers through the American embassy’s diplomatic pouch, to which journalists had access, and that channel proved effective not only at getting these editions into the country but also at getting manuscripts of new material out of it. The Proffers also were one of the very few outlets to the western world for Nadezhda Mandelstam, Osip’s widow, whose memoirs, which created a sensation in the west (her Mozart and Salieri was an Ardis publication), also left her both under virtual house arrest in Moscow and a pariah to the literary establishment there.

In 1972, they brought a writer along with his work to the west when they helped get Joseph Brodsky out of the Soviet Union and settled him in Ann Arbor, where he began his illustrious new life as a Russian-American poet. He was the first of a series of Russian writers who would make their way to this country with the Proffers’ help. (One particularly fond memory of mine is having helped Brodsky study for his citizenship exam. He had a kind of fetish about the Bill of Rights.)

The Proffers regularly traveled to the Soviet Union, until they were banned in 1979. I went along with them on one of these trips, and saw firsthand how indispensable they and their work were to the literary community there. Tourists were only allowed ten-day visits back then; we spent five days in Moscow, five in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg again), running more or less nonstop from apartment to apartment, often evading Soviet operatives who were tailing us.

It was heartbreaking to see what impoverished lives these writers led, and how constrained their lives were (virtually none of them dared meet us outside a writer’s apartment), and how excited they were whenever the Proffers came to town. Every visit to every writer’s apartment was a combination business meeting where authors pitched manuscripts at Carl and blow-out, vodka-soaked party far into the night, these huge celebrations of literature and freedom tinged with sorrow.

It was highly disorienting to meet the flower of contemporary Russian writing on the 1976 trip I took. Every day, I encountered another hero or heroine: Sergei Dovlatov, Vasily Aksenov, Andrei Bitov, Lev Kopelev and Raisa Orlova, Viktor Erofeev…and Nadezhda Mandelstam. They were among the legions of writers who greeted the Proffers like gods—nearly 40 years later, recalling the looks on their faces still brings tears to my eyes.

I mention all this to give a little context to my Nabokov memories. The Proffers often stopped off at Montreux to see the Nabokovs when coming from or going to the Soviet Union. And if not, they would always write to let the Nabokovs know they were about to travel there. Before every trip, they would get a letter with a substantial sum of money from Vladimir and Véra, asking them to give as they saw fit to “a dissident family” in need. Carl would show us these letters by way of explaining to us that Nabokov’s public posture was a fiction.

The Nabokovs made another, arguably more substantial contribution through Ardis to the walled-off Russian literary community. In the late 1970s, we reissued all of Nabokov’s Russian fiction in the original, and these editions were hugely popular in the Soviet Union. And when Ardis published Nabokov’s translation into Russian of Lolita, it was a sensation. I can still remember seeing these books—particularly Lolita, which every serious Russian student of literature knew of but had never been able to read—being lovingly handled by our poor Soviet friends, and being passed hand to hand with the same reverence and care with which they handled their beloved editions of Mandelstam and Tsvetaeva.

Ardis, as you might expect, is no longer in business, having mercifully been delivered of its reason for being by glasnost and its aftermath. For me, it has faded to the status of fond, ever-dimming memory—certainly among the most marvelous memories of my youth. Reading The Secret History brought it roaring back to life—a marvelous little gift I never expected to receive when I downloaded my copy.

Originally a graduate student in one of Carl Proffer’s courses at the University of Michigan, Fred Moody went on to work at Ardis Publishers from 1974 to 1980. After Ardis, Moody was a journalist in the Pacific Northwest for two decades. The author of I Sing the Body Electronic: A Year with Microsoft on the Multimedia Frontier, he is currently editor-in-chief at Anvil Academic, publisher of digital scholarly research.

———

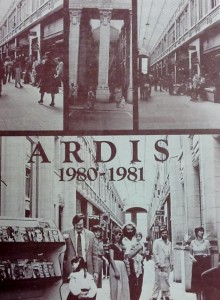

Images courtesy Fred Moody. Top photo: detail from an Ardis catalog cover. In the image from the lower half, adults from left to right are: Carl Proffer, Ellendea Proffer, Marysia Ostafin, Fred Moody, Igor Efimov, and Marina Efimov. Top photo: a collection of Ardis Publishers editions of Nabokov’s works.